Our kindergarten religious school teacher had given me and my classmates each a flag to carry as we marched in the processional. The flag, I remember, was blue and white: with two blue stripes against a white background, and in the center, a big, blue Jewish star. I took the flag in my hand, joined the parade, and waved it to my heart’s content. I was so filled with joy, I could have done cartwheels down the aisles. And although I did not know what flag I was waving, I knew in the depths of my heart that this flag was my flag – that blue and white were my colors.

This past week, Jews all around the world celebrated Yom HaAtzmaut, Israel’s Independence Day. And this year, it was a milestone anniversary, marking 75 years since that iconic moment when David Ben-Gurion – standing at a long dias, with a portrait of Theodor Herzl hanging above his head – read the Declaration of Independence aloud into a tinny microphone, and then a rabbi, his voice trembling with emotion, stammered his way through the shehechiyanu blessing, as Jews all around the world crouched beside their radios and wept with tears of joy.

If you’ve never celebrated Yom HaAtzmaut in Israel, it is a special experience. Israel is a small country – so seemingly everywhere you turn, there’s a celebration happening. There are people singing and dancing in the streets until all hours of the night, fireworks in every city, everyone dressed in blue and white, and Israeli flags and banners hanging from every street lamp. The next day, after sleeping off the previous evening’s festivities, the whole country, it seems, goes out to their nearest public park or garden – bringing with them their mangal (their portable grill) for an outdoor barbeque picnic. The air grows thick with the smell of burning charcoal and roasted meat – a scene that has often been compared to what it must have been like in ancient times when the Temple stood in Jerusalem, and worshippers would bring burnt offerings before God: an aroma that the Torah describes as “an odor pleasing to God,” a delight to the nostrils.

Looking back at that formative childhood memory, of marching around our synagogue’s sanctuary and proudly waving the Israeli flag, I recognize that a powerful feeling had been planted within me: a seed that was only just beginning to grow, that would continue to mature and blossom in the decades to come – and although I certainly did not have a word for it back then, I knew, in the depths of my heart, that I was a Zionist.

In recent years – and this past year, in particular – there has been much conversation in the Jewish world about the meaning of the word “Zionist.” If you listen to American political discourse, you might reasonably imagine that “Zionist” is a binary term: something you either are or you are not, an ideology that you are either for or against. This is so often our tendency in American political life: to reduce the conversation into two opposing camps, and to force each of us to pick which side we are on.

But of course, we Jews understand that the word Zionist is much more nuanced than this. In 2011, Moment Magazine published a symposium, a series of short essays written by prominent Jewish thinkers and leaders, on the question “What Does It Mean to be Zionist Today?” The range of answers was fascinating: a broad spectrum of ideas, some of them complementing one another, others of them contradicting one another. Clearly, in the Jewish community, Zionism is not some monolithic ideology which you are either for or against. Rather, the term is nuanced, textured, and layered – such that, although two Jews might both describe themselves as Zionists, they might each mean something completely different in their use of the word.

This past year, in particular, the meaning of the word Zionist has been up for debate. The State of Israel is undergoing enormous social change. The recent November election brought to power the most right-wing and most religiously observant governing coalition in the country’s history. Politicians who have trafficked in inflammatory rhetoric – against the Palestinians, against the Arab citizens of Israel, against the LGBTQ community, against Reform and Conservative Jews – have been appointed to the cabinet, at the helm of powerful government ministries. Perhaps most recognizably from the newspapers, a proposed set of judicial reforms would alter Israel’s system of checks and balances, diminishing the role of the Supreme Court, and effectively empowering the Knesset to pass whatever laws they might like without any judicial oversight.

In response to all of this, hundreds of thousands of Israeli citizens have taken to the streets in protest. And as a result of their demonstrations, the judicial reform has been put on pause – at least for now.

And also in response to all of this, many American Jews have found themselves wondering how they should relate to the State of Israel, and whether they should continue to call themselves Zionists. Over the past several months, Rabbi Schecter and I have facilitated dozens of group conversations in which TBS congregants have time and again wondered the same thing: Given all that is happening there, can we continue to support Israel? Do we recognize ourselves in the state? Should we continue to give our funds? Should we continue to send our children? Is it perhaps time, I have heard American Jews ask, to give up on the Zionist project entirely?

Let me say now, so that you don’t have to hold your breath, that I strongly believe that we should not give up on the Zionist project. And to help us understand why, let us first try to understand exactly what it is that we are talking about when we use the word “Zionist” – that term that, on its surface, seems to be a binary: something that you either are or are not, as clear as black and white (or, if you prefer, blue and white). Let instead try to scratch beneath the surface: to reach for a more nuanced, more textured understanding of the word, in order to help us make sense of our current political moment.

***

The word “Zionist” was coined in 1890 by a little-known Jewish writer from Vienna named Nathan Birnbaum. He was only a university student at the time, publishing a small student magazine devoted to politics and Jewish thought. And it was in that little magazine, published nearly a decade before Theodor Herzl would begin to write about the topic, that the word “Zionism” first appeared in print: Zionismus, in Birnbaum’s native German.

But even though Birnbaum gave us the word, he did not give us its definitive meaning. Especially in those early years, there were Zionists of many stripes.

There were those who used the term in a plain and simple way: seeking to establish a sovereign, independent Jewish State in the Land of Israel.

There were those, by contrast, who would call themselves only “territorialists”: seeking a Jewish state, but not convinced that it needed to be in the Land of Israel – happy to settle for any tract of land that could be made available, with supporters proposing as possible locations Uganda, Argentina, and (no joke) Buffalo, New York.

There were political Zionists, who believed that the most important factor in establishing a Jewish state would be persuading the leaders of the world’s most powerful nations to get on board with the project.

There were agricultural Zionists, who believed that the most important factor wasn’t convincing the nations of the world, but rather, moving to the Land of Israel – buying farms, planting orange groves, and “making the desert bloom.”

There were cultural Zionists, who believed that the most important thing would be fostering a Jewish cultural renaissance: a rich, new civilization rooted in the Land of Israel, where Hebrew songs, Hebrew plays, Hebrew art, and Hebrew philosophy would flourish, thereby enriching the culture not only of the Jewish state, but also, of the entire Jewish world – an antidote to assimilation.

There were American Zionists, who – uniquely in the tapestry of Zionist thought – felt comfortably at home in their nation of origin, and expressed their support not by moving to the Land of Israel, but rather, by providing philanthropy: first, by putting nickels in their little blue JNF tzedakah boxes, later, by investing in Israel bonds, and today, by securing congressional funding for Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system.

There were Zionists who were vociferously opposed to the diaspora – who believed, in Hebrew, in the principle of sh'lilat ha-golah – that 2000 years of homelessness had left the Jewish people weak, passive, with too many brains and not enough braun, that the Zionist project would never be complete until all the world’s Jews were safely relocated to the Land of Israel.

And there were those who were opposed to Zionism – who cared deeply about the Jewish people, but did not believe that our collective identity needed to be expressed through the establishment of a sovereign state.

As the Jewish historian Noam Pianko has observed: his field is not the history of Zionism, but rather, the history of Zionisms.

Just as, in those early years, the word “Zionist” did not mean just one thing, the same is true today. There are Religious Zionists, Ultraorthodox Zionists, religious pluralist Zionists, Greater Israel Zionists, liberal Zionists, Two-State Zionists, One-State Zionists, Christian Evangelical Zionists – the list goes on and on.

Given this range of meanings, it is easy to understand how two people might both describe themselves as Zionists, but each mean something completely different in their use of the word. In the years since Nathan Birnbaum first coined the term, it is a word that has (to frame it in the positive) been able to support a multiplicity of definitions. Or, alternatively (to frame it in the negative): it is a word that has suffered from a confusion of meaning.

To help us make sense of our current political moment, it might be helpful to look for a new word: to do as Nathan Birnbaum did and coin a new term – not to abandon the Zionist project, but rather, to find new language that clarifies exactly what it is that we feel for the State of Israel.

Near the end of his life, Theodor Herzl wrote a novel called Altneuland – a German title, which means: “The Old-New Land” (referring, of course, to the old Land of Israel, which would soon be made new). Following Herzl’s lead, perhaps what we need is not a new word, but rather, an old-new word – a word from the Jewish past that we revive and reclaim, to help us clarify our feelings for Israel.

To do so, let us look to the very beginning of the Zionist movement, before David Ben-Gurion, before Herzl, even before Birnbaum, to the very earliest stages of Jewish national aspiration – to a little group in Eastern Europe who are considered the forerunners and precursors of the Zionist movement: a group whose name in Hebrew was Hovevei Tzion, a term that means “the lovers of Zion.”

Hovevei Zion was a loose network of small, local Jewish groups that sprung up all across the Russian Empire in the wake of pogroms of the 1880s. They saw that their safety in Europe was at risk, and decided that the best solution would be to leave for the Land of Israel. They came from small towns and villages, had little money, had even less influence, and had received only a traditional Jewish education. Their strategy for establishing a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel was to work piecemeal – acquiring, in the words of their Hebrew motto, od eiz v’od dunam, buying “one more goat, and one more quarter-acre of land” at a time. They were not well organized; when they tried to plan a conference for all of their followers, a mere thirty people attended.

But what they lacked in organizational acumen, these “lovers of Zion” made up for both in passion and in courage. In 1882, a group of ten Hovevei Zion activists packed what little they had, left the Russian Empire, moved to the Land of Israel, and established the town of Rishon LeTziyon – the first new Hebrew city.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, Theodor Herzl – who had been raised in a well-to-do, assimilated Jewish family in the big city of Budapest, and had himself never personally experienced the kind of anti-Jewish violence that his coreligionists in the Russian Empire had endured – Herzl, more than a decade after the founding of the first Hebrew city, suddenly was awakened to the threat of European antisemitism – when Alfred Dreyfus, a high ranking Jew in the French military, was wrongly accused of espionage. Herzl quickly sprung into action, trying to convince the most influential Jews of Western Europe – the biggest philanthropists, the most important businessmen, the chief rabbis of major cities – to support the establishment of a Jewish state.

Herzl decided to organize a conference, and invited all these influencers to attend. But one by one, they each said no – afraid that this political activity might jeopardize their standing in their home countries.

With the conference fast approaching, and no prominent Jews planning to attend, Herzl decided to instead turn his attention elsewhere – seeking not a handful of wealthy and influential supporters, but rather, a vast swath of poor, marginal, but nevertheless deeply passionate Jews whom he had heard about, a group that had already for quite some time been making slow progress towards establishing a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel: a group known as Hovevei Zion, “the lovers of Zion.”

It was a perfect pairing. With Herzl’s political acumen and financial connections, and Hovevei Zion’s sheer numbers and fervent belief in the cause, the conference – which would later be known as the First Zionist Congress – was an enormous success, what the scholar Daniel Polisar has referred to as “the most politically significant meeting of any group of Jews in the last 1,800 years.”

***

Today, when we think about Zionism, we think about Herzl. What if, instead, in our search for a new, more helpful term to describe our feelings for the State of Israel, we looked not to Herzl, but rather, to his partners? What if, instead of using the ambiguous word “Zionists,” those of us who care deeply about the State of Israel instead referred to ourselves as Hovevei Zion, as “lovers of Zion”?

Love, after all, is a complex emotion. It has room both for critique and for admiration, both for anger and for care.

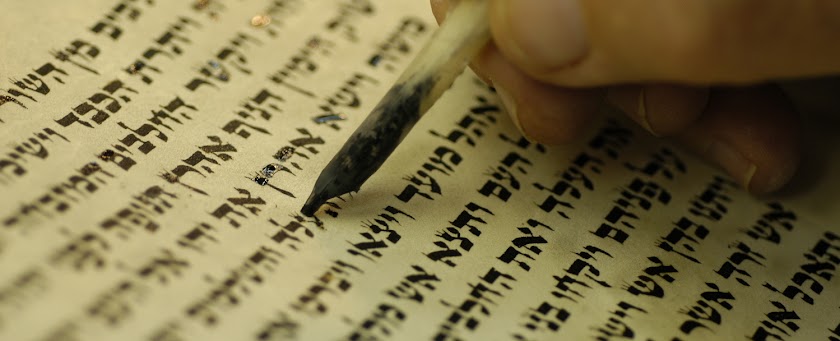

Love, after all, is what all those hundreds of thousands of Israelis have been expressing as they take to the streets week after week in protest. They are out there not because they can’t stand their country, but rather, because they love it. Perhaps you’ve seen the stirring images of the protestors. They are out there not in pink hats, like at the 2017 Women’s March; they are out there (and, to be clear: with no equivalence between the Women’s March and what I’m about to describe) – the protestors are out there not waving the Confederate Flag, like at the January 6th attack on the Capitol. Rather, they are out there by the hundreds of thousands waving the Israeli flag: expressing their patriotism, their love of the country that they, and I, and I hope many of us hold so dear; showing that they are not giving up on this place, and neither should we; showing that they are Hovevei Zion – lovers of Israel, proudly waving the flag, a sea of blue and white.

This, after all, is the sensation that I felt when I was five years old and marching around the sanctuary of our synagogue; the feeling that I did not yet have a word for as I was proudly waving the flag; the feeling not only that this flag was my flag, and that blue and white were my colors, but rather, something much deeper than that: a feeling of love for the Jewish people – the feeling, though I did not yet have the words, that I was a Hoveiv Zion.

This is why, when we recite Israel’s national anthem, we lift our voices and sing: kol ‘od balevav penimah / nefesh Yehudi homiyah / … ‘od lo avdah tikvatenu. “As long as in the heart within, the Jewish soul still yearns… then our hope is not yet lost.”

|

| Israelis protesting the judicial reform |