I recently got a call from a close friend whose father had died several years ago. My friend and his family were now cleaning out his old childhood home, helping to prepare his mom to move into a smaller place. He was calling to tell me about the strange experience of cleaning the house, how he felt haunted by memories of his dad -- how old pictures, or handwritten notes, or school report cards, or art projects that had once hung on the fridge brought his father so vividly to mind.

My friend told me that it was a windy weekend while they were clearing out the house -- and that each time he stepped outside to load another box into the U-Haul truck, he felt as if his dad was swirling around him in the wind. And finally, when the last room had been cleared, when the boxes were all packed up and loaded into the truck, when the mezuzah had been taken down from the front door, he and his family went to close the door to his childhood home for what he thoughts would be the last time. But as the latch began to click into the doorframe, a strong gust of wind blew up from the street, and the door went flying open. It felt, he said, as if his dad’s spirit just couldn’t bear to leave the old house behind. My friend told me: “I know that my dad wasn’t actually in that gust of wind, but I couldn’t help but cry. It just felt so real. Is that crazy?” he asked.

We can’t say for sure where the dead go after they have died. It is perhaps the most perplexing problem in the human condition. It is not a question that can be answered by empirical observation. It is not a question that can be addressed by reasoning or logic. Any possible answers lie beyond the horizon of human understanding -- outside the boundaries of what we can know for certain.

Where empirical observation fails, faith and belief must suffice. Some anthropologists suggest[1] that this is the very basis of religion: the longing to understand things that are just beyond our understanding -- to know where it is that we come from, and where it is that we go.

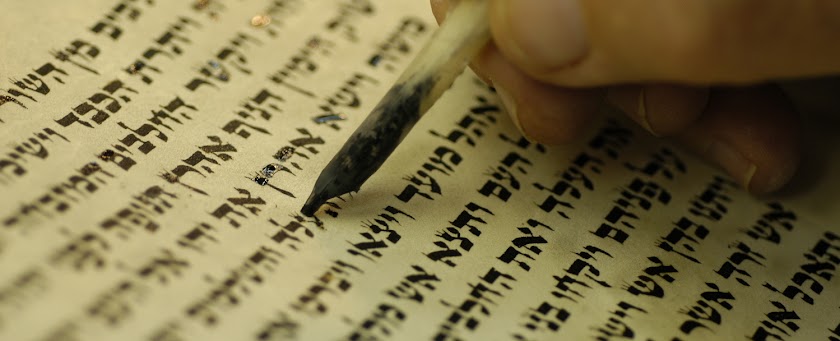

Jewish tradition is full of images of how the dead continue to inhabit the world of the living. One tradition[2] teaches that in the days immediately after a person dies, her soul continues to linger on earth -- confused about how to exist without a body, unsure of where to go next, visiting the people and places that she knew in her life. Another tradition[3] teaches that by saying Kaddish, we, the living, help the souls of the dead to find their way to the next world. Still another tradition[4] teaches that the dead can visit us in our dreams, advise us in our affairs, even intercede on our behalf for the betterment of our lives.

Since the Enlightenment, many Jews have kept their distance from beliefs such as these. We have difficulty integrating anything that isn’t able to be proved.

But we don’t have to be naive or foolish to understand what it is that our tradition is trying to express with each of these images. We don’t have to take these claims literally to understand the message. Judaism affirms that the dead, even after they have died, continue to be present in the world of the living. In our memories, they are entirely vivid. When we long for them, they are present to us -- present, by way of their absence. They even continue to influence our world. Our actions continue to be guided by our memories of them. Our choices are still influenced by the place they occupy in our hearts.

Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, of blessed memory, used to tell a story[5] of how his father continued to act in the world, even long after he had died. Schacter-Shalomi had a complex relationship with his father. When he was alive, his father would keep his feelings pent up, let them fester, and release them in fitful outbursts of anger. One afternoon shortly after his father had died, Schacter-Shalomi was driving down the highway, having just taught a class at a local yeshivah. He was unhappy with how the class had gone, and as he was driving, Schachter-Shalomi was stewing about the experience, letting his anger fester and grow -- just as his father had shown him to do. Immediately, Schachter-Shalomi pulled the car over to the side of the road, got out, and said out-loud to his father, as if he were standing right there next to him: “Papa -- you spent your whole life showing me how to explode with anger. But this is one lesson I don’t need anymore. This one, you can keep.”

Schachter-Shalomi felt full well his father’s still very real presence in his life. In releasing himself from his anger, in letting go, he continued to learn from his father -- in this case, by not following his father’s example. Is this not, on some level, a negative example of how the dead are able to intercede in the affairs of the living?

On Sukkot, we Jews participate in the practice of ushpizin. Ushpizin is an Aramaic word meaning “guests” -- and it refers to the practice, originated by the Kabbalists, of inviting guests into our Sukkah. In traditional practice, each day of Sukkot corresponds to one of seven biblical figures, whom we invite into the Sukkah on his or her particular day, in hopes that we might learn a spiritual quality from that guest. On the first day of Sukkot, we invite Abraham into our sukkah, in hopes that we might mirror his quality of hospitality to guests. On day two, we invite Isaac into our Sukkah, in hopes that we might learn from him how to feel awestruck before God. And so on.

On this last day of the Sukkot holiday, we might practice a different kind of ushpizin -- a different way of welcoming guests -- not by inviting biblical figures to come and celebrate with us, by rather, by inviting in our deceased loved ones to join us in this chapel. We invite her in -- and hope to mirror her quality of an inquisitive mind. We invite him in -- and hope to learn how not to let our anger fester and explode. We invite these ushpizin -- these guests -- into our celebration of Sukkot, because we know that they are with us, even when we don’t invite them in. They are with us, even when we are unaware of the role they continue to play in our lives. Our dead are never really gone, our tradition teaches. The space between the living and the dead is “a window, not a wall.”[6]

A short detour, by way of conclusion: Sarah Ruhl is a playwright who has published a book called One Hundred Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write. In that book, she writes about what happens when an actor opens up an umbrella on stage.[7] We know that it isn’t actually raining on the stage. But when that umbrella opens, it conjures for us the experience of rain. When the actor lowers the umbrella and shivers, we believe that she is getting cold and wet. We believe in the rain, even though we know plain and clear that the rain isn’t really there.

To ask, “Is it raining on this actor?” would be to ask the wrong question. That is a question of truth or falsehood, when the empirical truth of whether it is actually raining is entirely inconsequential.

Instead, we ought to ask a question not of truth or falsehood, but rather, of meaning.[8] “Does watching this actor lower her umbrella cause us to shiver, to remember what it’s like to stand out in the cold and the rain? Does seeing this non-reality play itself out on stage allow us to access the actual reality of being soaked to the bone, of feeling exposed to the elements?” These are not true/false questions -- but rather, questions of meaning. Does the combination of that real umbrella and the false rain give us access to a meaningful experience?

So what should we tell my friend who recently moved out of his childhood home? Is it crazy to think that the wind blowing the door open was actually his father?

We cannot say for sure. The answer is simply beyond the realm of human reasoning.

But maybe we’re asking the wrong question. Perhaps we shouldn’t be asking the true/false question of: “Was that actually my father?” Perhaps instead we should ask a question of meaning: “When the wind wraps itself around you, do you remember what it felt like to be held in your father’s arms? When the wind blows the door open, does the lifetime of memories created in that house come pouring out -- unable to be contained?”

These are questions we can answer. These are questions that, quite frankly, are far more interesting than a simple test of truth or falsehood. This is where feeling resides. This is where meaning is made. This is where comfort springs. This is where healing begins.

And so we practice the Jewish art of ushpizin -- of inviting our deceased loved ones into our sukkot celebration -- even though we cannot empirically prove that they have entered into our sukkah. Nevertheless, we sense them. Nevertheless, we feel their presence. We continue learn from their lives. We carry them with us always. We believe that, in some way, they continue to remain with us -- and that experience adds meaning to our lives. Why on earth would we need to prove that?

______

[1] Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens, p. 266-267.

[2] BT Sanhedrin 47b

[3] BT Sanhedrin 104a

[4] Finkel, Avraham Yaakov. The Book of the Pious, by Rabbi Yehudah HeChasid, p. 223.

[5] Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman. “On the Afterlife” (audio recording).

[6] Raphael, Simcha Paull. “Grief and Bereavement,” in Jewish Pastoral Care, ed. Friedman, p. 426.

[7] Ruhl, Sarah. One Hundred Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, p. 6-7.

[8] For more on these competing frameworks, see Rabbi Larry Hoffman’s soon-to-be-published essay, “Limits, Truth, and Meaning” (originally delivered as a lecture at the Shechinah conference in the mid 1980s).

My friend told me that it was a windy weekend while they were clearing out the house -- and that each time he stepped outside to load another box into the U-Haul truck, he felt as if his dad was swirling around him in the wind. And finally, when the last room had been cleared, when the boxes were all packed up and loaded into the truck, when the mezuzah had been taken down from the front door, he and his family went to close the door to his childhood home for what he thoughts would be the last time. But as the latch began to click into the doorframe, a strong gust of wind blew up from the street, and the door went flying open. It felt, he said, as if his dad’s spirit just couldn’t bear to leave the old house behind. My friend told me: “I know that my dad wasn’t actually in that gust of wind, but I couldn’t help but cry. It just felt so real. Is that crazy?” he asked.

We can’t say for sure where the dead go after they have died. It is perhaps the most perplexing problem in the human condition. It is not a question that can be answered by empirical observation. It is not a question that can be addressed by reasoning or logic. Any possible answers lie beyond the horizon of human understanding -- outside the boundaries of what we can know for certain.

Where empirical observation fails, faith and belief must suffice. Some anthropologists suggest[1] that this is the very basis of religion: the longing to understand things that are just beyond our understanding -- to know where it is that we come from, and where it is that we go.

Jewish tradition is full of images of how the dead continue to inhabit the world of the living. One tradition[2] teaches that in the days immediately after a person dies, her soul continues to linger on earth -- confused about how to exist without a body, unsure of where to go next, visiting the people and places that she knew in her life. Another tradition[3] teaches that by saying Kaddish, we, the living, help the souls of the dead to find their way to the next world. Still another tradition[4] teaches that the dead can visit us in our dreams, advise us in our affairs, even intercede on our behalf for the betterment of our lives.

Since the Enlightenment, many Jews have kept their distance from beliefs such as these. We have difficulty integrating anything that isn’t able to be proved.

But we don’t have to be naive or foolish to understand what it is that our tradition is trying to express with each of these images. We don’t have to take these claims literally to understand the message. Judaism affirms that the dead, even after they have died, continue to be present in the world of the living. In our memories, they are entirely vivid. When we long for them, they are present to us -- present, by way of their absence. They even continue to influence our world. Our actions continue to be guided by our memories of them. Our choices are still influenced by the place they occupy in our hearts.

Rabbi Zalman Schacter-Shalomi, of blessed memory, used to tell a story[5] of how his father continued to act in the world, even long after he had died. Schacter-Shalomi had a complex relationship with his father. When he was alive, his father would keep his feelings pent up, let them fester, and release them in fitful outbursts of anger. One afternoon shortly after his father had died, Schacter-Shalomi was driving down the highway, having just taught a class at a local yeshivah. He was unhappy with how the class had gone, and as he was driving, Schachter-Shalomi was stewing about the experience, letting his anger fester and grow -- just as his father had shown him to do. Immediately, Schachter-Shalomi pulled the car over to the side of the road, got out, and said out-loud to his father, as if he were standing right there next to him: “Papa -- you spent your whole life showing me how to explode with anger. But this is one lesson I don’t need anymore. This one, you can keep.”

Schachter-Shalomi felt full well his father’s still very real presence in his life. In releasing himself from his anger, in letting go, he continued to learn from his father -- in this case, by not following his father’s example. Is this not, on some level, a negative example of how the dead are able to intercede in the affairs of the living?

On Sukkot, we Jews participate in the practice of ushpizin. Ushpizin is an Aramaic word meaning “guests” -- and it refers to the practice, originated by the Kabbalists, of inviting guests into our Sukkah. In traditional practice, each day of Sukkot corresponds to one of seven biblical figures, whom we invite into the Sukkah on his or her particular day, in hopes that we might learn a spiritual quality from that guest. On the first day of Sukkot, we invite Abraham into our sukkah, in hopes that we might mirror his quality of hospitality to guests. On day two, we invite Isaac into our Sukkah, in hopes that we might learn from him how to feel awestruck before God. And so on.

On this last day of the Sukkot holiday, we might practice a different kind of ushpizin -- a different way of welcoming guests -- not by inviting biblical figures to come and celebrate with us, by rather, by inviting in our deceased loved ones to join us in this chapel. We invite her in -- and hope to mirror her quality of an inquisitive mind. We invite him in -- and hope to learn how not to let our anger fester and explode. We invite these ushpizin -- these guests -- into our celebration of Sukkot, because we know that they are with us, even when we don’t invite them in. They are with us, even when we are unaware of the role they continue to play in our lives. Our dead are never really gone, our tradition teaches. The space between the living and the dead is “a window, not a wall.”[6]

A short detour, by way of conclusion: Sarah Ruhl is a playwright who has published a book called One Hundred Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write. In that book, she writes about what happens when an actor opens up an umbrella on stage.[7] We know that it isn’t actually raining on the stage. But when that umbrella opens, it conjures for us the experience of rain. When the actor lowers the umbrella and shivers, we believe that she is getting cold and wet. We believe in the rain, even though we know plain and clear that the rain isn’t really there.

To ask, “Is it raining on this actor?” would be to ask the wrong question. That is a question of truth or falsehood, when the empirical truth of whether it is actually raining is entirely inconsequential.

Instead, we ought to ask a question not of truth or falsehood, but rather, of meaning.[8] “Does watching this actor lower her umbrella cause us to shiver, to remember what it’s like to stand out in the cold and the rain? Does seeing this non-reality play itself out on stage allow us to access the actual reality of being soaked to the bone, of feeling exposed to the elements?” These are not true/false questions -- but rather, questions of meaning. Does the combination of that real umbrella and the false rain give us access to a meaningful experience?

So what should we tell my friend who recently moved out of his childhood home? Is it crazy to think that the wind blowing the door open was actually his father?

We cannot say for sure. The answer is simply beyond the realm of human reasoning.

But maybe we’re asking the wrong question. Perhaps we shouldn’t be asking the true/false question of: “Was that actually my father?” Perhaps instead we should ask a question of meaning: “When the wind wraps itself around you, do you remember what it felt like to be held in your father’s arms? When the wind blows the door open, does the lifetime of memories created in that house come pouring out -- unable to be contained?”

These are questions we can answer. These are questions that, quite frankly, are far more interesting than a simple test of truth or falsehood. This is where feeling resides. This is where meaning is made. This is where comfort springs. This is where healing begins.

And so we practice the Jewish art of ushpizin -- of inviting our deceased loved ones into our sukkot celebration -- even though we cannot empirically prove that they have entered into our sukkah. Nevertheless, we sense them. Nevertheless, we feel their presence. We continue learn from their lives. We carry them with us always. We believe that, in some way, they continue to remain with us -- and that experience adds meaning to our lives. Why on earth would we need to prove that?

______

[1] Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens, p. 266-267.

[2] BT Sanhedrin 47b

[3] BT Sanhedrin 104a

[4] Finkel, Avraham Yaakov. The Book of the Pious, by Rabbi Yehudah HeChasid, p. 223.

[5] Schachter-Shalomi, Zalman. “On the Afterlife” (audio recording).

[6] Raphael, Simcha Paull. “Grief and Bereavement,” in Jewish Pastoral Care, ed. Friedman, p. 426.

[7] Ruhl, Sarah. One Hundred Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, p. 6-7.

[8] For more on these competing frameworks, see Rabbi Larry Hoffman’s soon-to-be-published essay, “Limits, Truth, and Meaning” (originally delivered as a lecture at the Shechinah conference in the mid 1980s).