In many successful musicals, there’s a particular storytelling device that is often key component. It is called the “I want” song. It’s that song, usually sung relatively early on in the musical, where the protagonist articulates the thing that they deeply want. It is a moment of self-revelation, where the audience comes to understand something important about the protagonist -- the deepest yearning of their heart, the dream that they have for themself, the world that the protagonist would like to inhabit. And typically, after the “I want” song, the rest of the musical unfolds around that character’s quest to achieve the thing that they want.

A classic example comes from a musical composed by none other than Leonard Bernstein himself -- the masterpiece West Side Story. After the overture has concluded, after we are introduced to the rival gangs of the Jets and the Sharks, the second song in the musical is an “I want” song. Tony, one of our protagonists, sings the song “Something’s Coming” -- revealing to the audience his feeling that life has more in store for him than his daily humdrum routine. Here are a few of the lyrics: “There's something due any day. I will know right away, soon as it shows. … It's only just out of reach -- down the block, on a beach, under a tree. … Something's coming. I don't know what it is -- but it is gonna be great.” Now that we’ve seen the deepest desire of Tony’s heart, the rest of the story can unfold in all its tragic beauty.

This moment -- the “I want” song, in musical theatre -- can also be traced onto other powerful forms of storytelling. The famous scholar of mythology, Joseph Campbell, described the literary pattern known as “the hero’s journey.” One element of the hero’s journey is “the call to adventure” -- that moment in the story when the protagonist realizes that the world they have always known is somehow too small, and begins to feel the pull towards something different, something new, something unknown. It might be Tony in West Side Story singing “Something’s Coming,” or Ishmael in Moby Dick, feeling “the damp November in [his] soul” and feeling it high time that he set off to sea, or Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, grown tired of sepia-toned Kansas, where “all the world is a hopeless jumble,” imagining a life that is “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” These are people dreaming of a life that is as yet unknown, an existence that is just beyond the horizon. “It’s only just out of reach -- down the block, on a beach. … Something’s coming.”

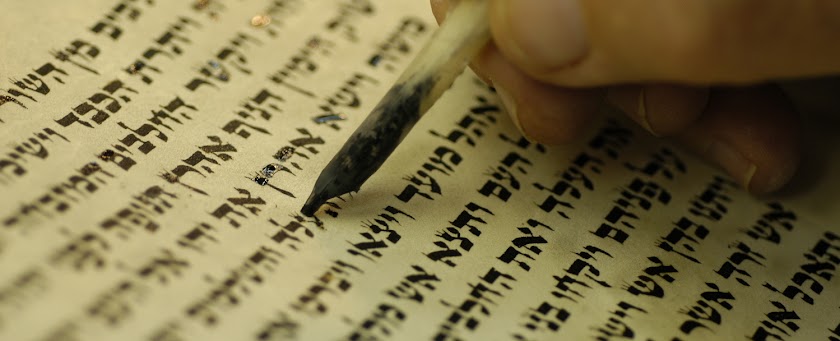

In this week’s Torah portion, we meet a character who also feels that something’s coming -- who also dreams of a world that is beyond everything that she has ever known: our matriarch, Rebecca. In the Torah narrative (Genesis 24), Rebecca’s story is told from the perspective of her soon-to-be father-in-law, Abraham. It goes something like this: Abraham, we might recall, is ready to find someone for his son Isaac to marry. And so Abraham sends the chief servant of his household back to the old country, back to Mesopotamia, where Abraham had grown up, to try and find a suitable mate for Isaac. Upon his arrival in the old country, the servant happens upon Rebekah drawing water from the town well. When he asks her for a sip, she not only draws water for him, but also for all of the camels in his caravan. From this gesture, the servant sees that Rebekah is someone who is generous and giving -- and feels that she is the kind of person Abraham had sent him to find: a perfect match for Isaac.

When Rebecca’s story is told from this perspective, the primary character traits that come across are her generosity, her caring, and her kindness. And indeed, these are praiseworthy qualities.

But when we tell the story from Rebecca’s point of view, a very different picture of her emerges. Let us imagine it now: Rebecca has lived her whole life as part of a small and tight-knit family in Mesopotamia. One day, a stranger arrives from far away Canaan. While the other villagers see him as a dirty, foreign beggar, Rebecca sees in him an interesting outsider to whom she is naturally drawn. His caravan of camels is laden not just with goods and provisions, but also with stories of far away places. He comes on a mission, on a quest. And when this voyager eventually proposes that Rebecca leave behind her family to accompany him on a long journey to an unknown place, where she will marry a man she’s never met before, who worships an invisible God -- Rebecca immediately accepts. Eileich, she says in Hebrew. “I’ll go.”

Told from her perspective, Rebecca’s story is not only about generosity and kindness, but also, is about bravery, the call to adventure, the search for something more than the daily humdrum life that she has always known. We might imagine Rebecca, moments before she meets this voyager, quietly humming to herself the words that Tony sings in West Side Story: “Something’s coming. … I don’t know what it is -- but it is gonna be great.”

Our sages have long noted that, in many ways, it is not Abraham and Sarah’s son, Isaac, who serves as the next link in the chain of tradition, but rather, it is their daughter-in-law, Rebecca, who inherits their spiritual legacy. Abraham and Sarah established this religion by famously heeding the call to adventure, when God said to them Lech lecha -- go forth from the place of your birth to a land that I will show you. Rebecca, one generation later, does the very same thing -- saying eilech, “I’ll go,” leaving behind her family and the home she has always known, her eyes gazing towards the horizon. Also in the next generation, Jacob, Rachel, and Leah will go forth on a journey. Of all our founding fathers and mothers, it is only Isaac who never once leaves the place of his birth. He is born in Canaan, he will spend his whole life in Canaan -- and there, he will die and will be buried.

We note this, not to speak ill of Isaac; there are plenty of good reasons why he never left the place of his birth. Rather, the point is that a central element that links all three founding generations is an eye that gazes towards the horizon, a feeling of spiritual restlessness, the willingness to leave behind the familiar. This, it seems, is a core insight of the Jewish spiritual tradition: the feeling that there is something more out there, something beyond the humdrum existence of our everyday lives, the feeling that “Something’s coming.”

This is what the act of prayer is all about -- to help attune us to the wisdom of our tradition, a wisdom put forth by Abraham and Sarah and carried on by Rebecca: the wisdom that our life and our world can be so much more than meets the eye. Prayer is not the act of reciting ancient words, in a foreign language, in hopes that they might somehow please an invisible God. Rather, prayer is the act of getting in touch with the yearnings of our heart, of keeping our gaze towards the horizon, of dreaming of a world that is as yet unknown. If we listen carefully, we just might hear the song that is embedded deep within the human soul, telling us that there is something “only just out of reach -- down the block, on a beach, under a tree. … I don't know what it is -- but it is gonna be great.”