There’s a famous mental exercise that anthropologists use to study human societies. In the exercise, they imagine that an alien, who has never experienced life on earth, visits a certain country to observe their culture. Everything that the alien sees, she’s seeing for the first time. And looking at the world through the alien’s eyes, anthropologists are better able to scientifically observe the quirky behaviors that define human culture.

Let us act as amateur anthropologists for a moment. Let us pretend that an alien has come to earth for the first time. Her flying saucer happens to land in a country called the United States of America, on a holiday weekend called Thanksgiving. The alien doesn’t speak English, so she doesn’t know what this word “Thanksgiving” means. But she looks around her, and tries to understand the meaning of the holiday based on her observations. She sees that we Americans prepare a giant feast, where we eat and drink to excess. We go shopping -- and collectively, we spend over eight billion dollars. Occasionally, people are killed in a shopping stampede. On TV, we watch a lavish parade where celebrities are pulled down the street on glittering floats, followed by a competition where we award fancy dogs with prizes based on which one is the showiest. And over the weekend, we cheer for our favorite college football teams to beat our most hated rival.

Observing these rituals, our alien visitor would be unlikely to guess the meaning of the word “Thanksgiving.” In fact, she might reasonably conclude that Thanksgiving is devoted to obsessing over things we want, rather than cultivating gratitude for the things we have.

Don’t get me wrong. I love Thanksgiving. I love gathering with family and cooking together. I love staying up late playing boardgames in front of the fireplace. I even love the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, the sheer joy on my child’s face -- and I admit, on my face too -- as a three-story-tall Elmo balloon goes floating down Sixth Avenue.

But I wonder about that alien observer. I wonder if there are ways in which we might help her to see -- to observe, through our behavior -- that Thanksgiving is intended to be a holiday of gratitude.

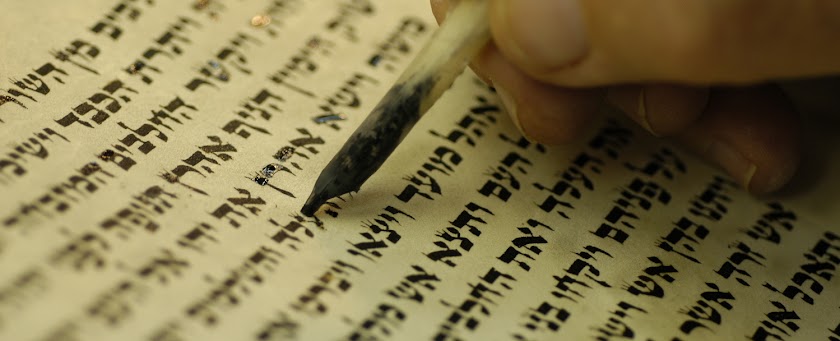

I’ve heard it said that the purpose of religion is to practice gratitude -- though, as is the case with Thanksgiving, this purpose sometimes gets lost in the trappings. The word “Judaism,” for example, literally derives from the Hebrew word for “gratitude.” We read in this week’s Torah portion the birth story of our religion’s namesake, Judah, and how his mother named him Yehudah, meaning, “I give thanks.” To be a Jew -- that is, to be descended from the Tribe of Judah -- means to give thanks, to practice gratitude.

This evening, I’d like to look back to the so called original Thanksgiving, that shared feast between the Puritans and the Wampanoag Tribe, to see what it can teach us about how to be a good Jew -- that is, to see what it can teach us about how to be good at practicing gratitude. Let us acknowledge up front that our popular imagination of that original Thanksgiving largely whitewashes the many centuries of mistreatment that indigenous people on this continent have suffered at the hands of European settlers. Nevertheless, the Puritans and Wampanoag did indeed enjoy relatively peaceful relations for nearly fifty years -- an unfortunately rare such example of cooperation and mutual respect. Their original Thanksgiving feast embodies two models of gratitude from which we can still derive wisdom today -- the model practiced by the Puritans, and the model practiced by the Wampanoag.

Let us start by examining the Puritans’ model of gratitude, which we might characterize as a gratitude of survival. The Pilgrims landed at the tip of Cape Cod in the fall of 1620. During their first brutal winter, more than half of their population died from exposure to the cold, scurvy, and contagious disease. Their prospects for survival on this continent looked pretty grim. That spring, they learned from the Wampanoag a few basic wilderness skills to help them adapt to their new environment: how to plant and harvest corn, a crop they’d never seen before; how to extract sap from maple trees; how to catch fish in the rivers; how to identify poisonous plants. That summer, they enjoyed a fruitful harvest. And in the fall, they organized a feast of gratitude that that first brutal winter was now behind them, that they might indeed have a chance of survival on this continent -- the first Thanksgiving.

It is said that the Pilgrims may have modeled their harvest feast on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. The Pilgrims, after all, were a religious community, and were highly literate in the traditions of the Hebrew Bible. They saw themselves as the New Israelites, liberated not from the slavery of Egypt, but from the Anglican Church. They saw North America as their New Promised Land -- their difficult Atlantic voyage and that first brutal winter on the continent as their 40 years of wandering in the desert. And just as the ancient Israelites celebrated their having survived by enjoying a festive Sukkot meal, so too did the Puritans establish the tradition of a harvest feast -- the first Thanksgiving.

This model of gratitude -- the gratitude of survival -- acknowledges the precariousness of life: the challenges of a harsh winter, the uncertainty of any harvest season. But the practice of gratitude is a choice. The Puritans might have just as easily felt despair that half their camp had died that first brutal winter. The Israelites, for their part, do indeed complain -- and complain at length -- about having to wander through the wilderness. These are reasonable feelings. When difficult times challenge us, we naturally tend towards anger and disappointment. Gratitude does not require that we ignore these feelings. Rather, it empowers us to harness these feelings to lessen our own suffering. Living with an awareness that life sometimes disappoints, we can learn not to take life for granted.

Would our Thanksgiving celebrations be made more meaningful if were felt more acutely the precariousness of life? God forbid there should be more suffering in our lives. But instead of focusing on enjoying what we have, could we spend part of Thanksgiving weekend getting in touch with what we’ve lost, acknowledging the ways in which we’ve suffered, and learning not to take life for granted -- celebrating that despite it all, here we are?

This is the gratitude of survival -- the gratitude of the Puritans: the gratitude of finding small blessings amidst life’s real challenges. Let us turn our attention now to the other participants in that first Thanksgiving feast, to the Wampanoag.

We might characterize the Wampanoag model of gratitude as an attitude of plenty. Over many centuries, the Wampanoag learned how to live in harmony with Mother Earth. They studied the natural world -- its weather patterns, animal behaviors, cycles of plant life, the movement of the stars and the sun -- and held them all in highest esteem. They learned to use every part of a slain deer: its meat for food, its skin for clothing, its bones for creating tools. Theirs was a thanksgiving not of having survived in a difficult environment, but rather a thanksgiving that the natural world provides exactly what is needed, that there are always plenty of resources to go around.

Our Jewish tradition, too, knows this model of gratitude -- the gratitude of plenty. Our best model of it may come from the Chanukkah story. Chanukkah could easily be cast as a story that expresses gratitude of survival. The Maccabees, after all, survived the cultural prohibitions that were placed upon them by the Syrian Greeks. But the Chanukkah story doesn’t end with survival. We all know the story: after the Maccabees returned from the battlefield to the Temple of Jerusalem and went to light to the menorah, there were only enough oil to last one night. But miraculously, the oil lasted for eight nights! The Maccabees might have chosen not to light the menorah at all -- knowing full well that there wasn’t enough oil. But instead, they adopted an attitude of plenty. Rather than obsessing over what they didn’t have, the Macabees celebrated what they did have -- an act of gratitude. They embodied the Jewish maxim: “Who is rich? The person who is happy with what he has” (Pirkei Avot 4:4).

The great Medieval Jewish ethicist, Rabbi Bachya ibn Pekuda, notes that a conundrum keeps us from more often adopting an attitude of plenty. The conundrum is that physical pleasures can never fully be gratified. For example, things that are tasty to eat continue to be tasty to eat, even after our hunger for them for has been satiated. The mouth and the stomach are not in sync -- and this keeps us from feeling satisfied with what we have.

How would our Thanksgiving celebration be made more meaningful if we adopted an attitude of plenty -- if, instead of eating to excess, we ate a normal sized meal, to acknowledge that we daily have more than enough? What if instead of spending eight billion dollars on Black Friday, and by comparison, a paltry $170 million on Giving Tuesday, the numbers were reversed?

And so we see two models of gratitude: the gratitude of survival, embodied by the Pilgrims and the holiday of Sukkot; and the gratitude of plenty, embodied by the Wampanoag and the holiday of Chanukkah. The former can help us not to take life for granted; the later can help us to experience life feeling that what we have is enough.

If our alien anthropologist saw us adopting these two models of gratitude, she might come to understand the true meaning of Thanksgiving. And in so doing, we might come to understand the true meaning of being Jewish -- which is, to be descended from the Tribe of Judah, whose name means, “I am grateful.”

Kein y’hi ratzon -- may this be so.