And while many have called for such a reconciliation, few have provided any useful roadmaps for doing so. As Rabbi Blake shared last week: when the clothing manufacturer The Gap released an ad suggesting that national reconciliation might be as simple as zipping together the two sides of a hooded sweatshirt, the company were excoriated as naive to the depth of the problem. To heal our nation’s wounds, we will need a vision that far exceeds the perception of The Gap’s marketing director.

Such a vision was offered this week from one of the most unlikely of places. This past Saturday night, in front of a small, socially distanced audience, in studio 8H at Rockefeller Plaza, the comedian Dave Chapelle took the mic as the guest host of Saturday Night Live. Chapelle has hosted SNL only once before -- and the last time was at another highly divided moment in our country’s history: on the Saturday immediately after the 2016 presidential election.

If you’ve ever seen Chapelle’s work -- including, most famously, his sketch comedy series The Chapelle Show, which, among other things, takes a satirical jab at race relations in the United States -- you know that he regularly brings his sharp wit to comment on American politics, culture, and society. And this past Saturday night, his opening monologue did exactly that.

But amidst all of his edgy observations and punch lines, perhaps the most powerful moment in the 12-minute routine was when Chapelle, who is a self-described liberal, took a more serious tone, and turned directly to the camera for a moment of honest reflection. Addressing the members of the viewing audience who align with him politically, Chapelle said: “Remember when I was here four years ago? Remember how bad that felt? Remember that half the country, right now, still feels that way.”

What I found so refreshing about Chapelle’s comment was that it provided us with a clue about how to heal our deep national wounds. He asked the members of his viewing audience who were pleased with the election results to do something that is at once quite simple, and yet, at the same time, quite profound. He asked them -- and, by extension, all of us -- to try and put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, to remember how they feel. He asked us to try and remember the humanity of the people with whom we most strongly disagree, to try and channel their inner lives. While other public figures made well meaning but vague calls for national unity, Dave Chapelle told us how to do so: by trying to traverse the empathic distance between us, by trying to become moral travelers.

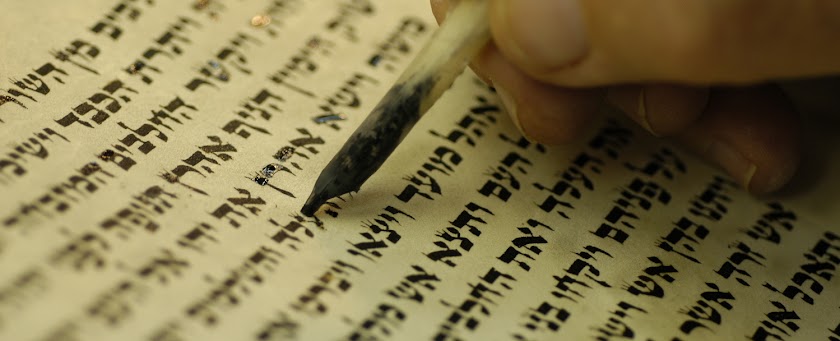

We find in this week’s Torah portion a similar dynamic. Two times, our Torah portion presents us with a well meaning but somewhat Pollyanna picture of former foes reunited in peaceful harmony. We see the half-brothers Isaac and Ishmael -- one, the progenitor of Judaism, the other, the progenitor of Islam -- reunited after nearly a lifetime of estrangement, as, together, they bury their beloved father, Abraham. The midrash (or ancient Jewish legend) adds that, just before his death, Abraham was reunited with his former lover, Hagar -- him, a Hebrew, her, an Egyptian, the future enslavers of the Hebrews, lovingly reconciled despite their past quarrels and their peoples’ future animosity.

And while both of these scenes of unity are lovely and encouraging, they are also not all that helpful. They give us something towards which to aspire, but provide little instruction as to how it might be achieved. The prophet Isaiah dreamed of a future, messianic time when former enemies would be united in peace: when the lion would lie down with the lamb -- when the snake and the child would play together, without the child trying to behead the snake or the snake trying to bite the child’s heels. It’s an admirable image. The only question is: how do we get there?

A different, less obvious scene in our Torah portion provides us with helpful instruction.

Our matriarch Rebecca is an undersung hero. If we celebrate her at all, we celebrate her for being generous and kind. We meet her this week, while she is standing beside a well. A stranger -- who turns out to be one of Abraham’s servants, a man named Eliezer -- arrives at the well. He is parched, having just made the long journey from where Abraham is living in the land of Canaan to here, Rebecca’s hometown in Mesopotamia. The dirty and dusty Eliezer asks Rebecca for a sip of water. She gladly obliges -- and unprompted, she further extends her generosity by dipping her bucket into the well and also providing water for all of Eliezer’s twelve camels -- no small task.

We remember Rebecca for this act of kindness -- for going out of her way to provide hospitality to a stranger. But this is only half the story. Because even more than she is generous, Rebecca shows herself to be incredibly brave. Impressed by Rebecca’s act of kindness, Eliezer proposes something preposterous to her. He mentions that he has traveled all this way on behalf of Rebecca’s distant cousin, Isaac -- and Eliezer proposes that Rebecca make the long journey back with him in order to marry Isaac.

Consider for a moment how absurd is this request. A strange man is asking Rebecca to follow him and his invisible God, travel thousands of miles across a scorching-hot desert to a foreign land, in order to marry a man she’s never met before. And shockingly enough, though she will have to learn a new language, adopt a new lifestyle, and practice a new religion -- Rebecca agrees to go.

In our era of deep polarization, we can learn from Rebecca’s bravery. It might often feel like we and the people with whom we disagree are not even living in the same country -- as if we are in our own little land of Canaan, and they, in far off Mesopotamia. It might often feel like a vast, scorching hot ideological desert divides us from one another. It might often feel as if the people with whom we disagree are not even our fellow Americans -- seeing one another as complete strangers, forgetting that, in fact, we are distant cousins.

Like Rebecca, if we are to traverse the empathic distance that separates us from one another, we will need both generosity and bravery -- bravery to leave behind the safe and comfortable ideological bubbles in which we’ve cloistered ourselves, and generosity to consider that the people with whom we most strongly disagree feel as certain in their beliefs as we might feel in ours.

In his widely acclaimed book The Righteous Mind, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt -- who grew up Jewish in Scarsdale, by the way -- examines how it is that equally smart and compassionate groups of people can find themselves so deeply divided by religion and politics. Each side, he points out, thinks that if only the other side would simply listen to reason, they would come around to the correct moral judgment -- our moral judgment.

But Haidt’s research shows that our moral judgments are not as grounded in pure logic as we might think. He examines certain taboos that vary from culture to culture. For example, Americans tend to be repulsed by the idea of eating dogs. Even though a thorough, logical examination might demonstrate that eating dog is no different from eating beef -- still, many of us hold this to be a moral red line. This, it turns out, is how most of our moral judgments are made. We inherit our moral standards from our surroundings -- and only after we have affirmed them do we employ the means of logic and reason to justify our beliefs. We are conditioned to use logic to fortify our own beliefs, rather than use logic to inspect them.

Haidt has identified six moral “flavors,” as he calls them. Any of us would affirm that each of these six moral flavors, when considered alone, is better than its opposite: it is better to exhibit care than to do harm, fairness is better than cheating, liberty is better than oppression, loyalty is better than betrayal, order [1] is better than chaos, and quality of life [2] is better than degradation. And while all of us would agree that each of these six flavors is better than its opposite, our culture wars begin when we start mixing flavors in the kitchen. Different groups prioritize and combine a different set of these flavors -- the way that Italian cooking relies on basil, while Indian cooking relies on cumin -- to the point that each social faction has its own distinctive moral cuisine.

Given this, it is easier to understand how equally smart and compassionate groups of people can come to such opposite conclusions about society’s most pressing questions. Given this, it is harder to dismiss the people with whom we disagree as merely ignorant or cruel. We are forced, instead, to remember each other’s humanity -- that we are not pariahs to one another, but rather, are distant cousins.

This is not to fall into total moral relativism. Our Jewish tradition affirms that even while the truth is always complex, the truth can be ascertained. Our tradition in general and the Talmud in particular is famous for going out of its way to explore every issue thoroughly on all sides -- making room for the opposing argument, giving credibility to the dissenting opinion. And only then, after all sides have been rigorously inspected and given honorable treatment -- only then is the decision of how to act finally made. Ours is not an argument for moral relativism; it is an argument for honorable treatment.

So let us hope to be like Rebecca -- to tap our deepest wellsprings of bravery and generosity. It may feel as if a vast, scorching-hot ideological desert separates us from one another. Nevertheless, we must find the courage to cross it. If not, then the expanse between us will seem to grow and the desert consume us all. So like Rebecca, let us fill our buckets with water, and give plenty to the camels as well. We have a long journey ahead.

_____

[1] Haidt uses the word “authority” -- but I have chosen a related word to better illustrate the binary.

[2] Haidt uses the word “sanctity” -- but I have chosen a more colloquial phrase.