Last Saturday morning, on Shabbat, while the members of Congregation Beth Israel of Colleyville, Texas, were celebrating a Bar Mitzvah service, a stranger, who had come into the synagogue from the cold, seemingly looking for some place in which to sit and warm himself with a hot cup of tea, suddenly pulled out a firearm in the middle of the service, and demanded, at gunpoint, that these Jews, whom he imagined to be the world’s puppet masters, secure the release of Aafia Siddiqui from federal prison -- holding the rabbi and three congregants hostage in their own sanctuary for more than eleven hours. It was a terrifying situation.

Late Saturday night, after the hostages eventually escaped unharmed, we all breathed a deep sigh of relief. But still, that night, I could not sleep. It all hit just a little too close to home. I could not stop thinking about the scene inside that sanctuary -- about the tension, the pressure, the fear. I could not stop thinking about the assailant, who reportedly asked the hostages how many kids each of them had, and shouted to the hostage negotiator outside the door: “Why are you going to leave seven children orphaned?” I could not stop thinking about the congregants of Beth Israel, who watched as their little shul, where they have eulogized their parents and given Hebrew names to their children, was broadcast on international television, surrounded by hundreds of FBI agents and SWAT teams. I could not stop thinking about the hostages’ families. Who had informed them of what was unfolding inside of the synagogue? Where were they throughout the ordeal, and who was with them? I could not stop thinking about the hostages themselves. What thoughts must have been racing through their head?

I share these painful images not as an act of voyeurism, but rather, because they haunt me. And I know that I am not alone in this feeling. For many of us, it has been all too easy this week to project ourselves into that terrifying situation -- to feel that it could have been us, to wonder how we would have reacted. Although the hostages escaped physically unharmed, the events of this past weekend have once again activated one of the Jewish people’s most deep-seated psychological traumas: our centuries-old fear for our safety in an all too often hostile world.

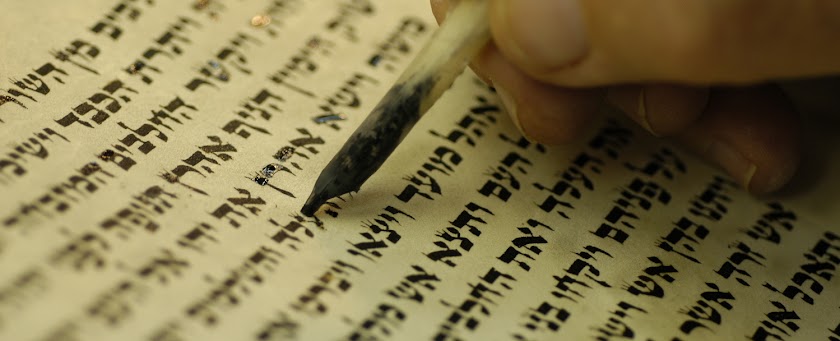

Earlier this week, a group of congregants gathered together and studied a passage from the biblical Book of Lamentations about being held hostage. Lamentations was written more than 2500 years ago -- so deeply rooted in history is our trauma. The passage from Lamentations argues that among all the possible crises that might befall a person, to be held hostage is among the worst -- because to be held hostage inflicts not only physical pain, but also psychological, emotional, and spiritual pain as well.

In the days since the hostages escaped, there has been much conversation in the Jewish world about how to protect our communities from physical pain. There will be continued security training for clergy and congregants; there will be increased funding for synagogues and other Jewish institutions to secure our campuses; there will be vital conversations about how to strike a proper balance between, on the one hand, welcoming strangers in from cold, and on the other hand, keeping our communities safe from strangers who would do us harm; there will be further efforts to educate our friends and neighbors about what anti-Semitism looks like, why it is sometimes hard to spot, and how best to combat it.

These conversations about how to keep our communities physically safe are critically important. And yet, as the passage from Lamentations reminds us, our physical safety is only part of the equation. If we are to effectively cope with our deep-seated trauma, then we must also be sure to invest in our emotional and spiritual wellbeing -- which is why we gather together on Shabbat.

We need each other right now. We need to be together, to hold one another. We need a space into which we can bring our pain, our fear, our sadness, our anxiety. We need to consider not only how we will protect ourselves when the world outside feels vulnerable, but also, how we will uplift ourselves when the world inside feels vulnerable. As one congregant put it so eloquently this week: we may need to carefully guard the doors of the synagogue -- but the doors of the ark must continue to remain wide open, so that we can pour out our hearts.

This Shabbat, we are invited to do exactly that. With the ark wide open behind me, and our hearts wide open as well, we kindle these lights for Shabbat…