One of my most cherished memories of the time I’ve spent in Israel comes from the year that my wife, Leah, and I lived in Jerusalem during my first year of rabbinical school. We had been there a little less than a week – settling into our apartment, wandering all over the city in search of its many hidden wonders, meeting my classmates, practicing our Hebrew.

The end of that first week was our first Shabbat in Israel, and the rabbinical school organized an outdoor Shabbat service for us on campus, in a lovely, shady garden overlooking the walls of the old city. It was a perfect Jerusalem summer night: a warm breeze, familiar Shabbat melodies, Leah and I – still just boyfriend and girlfriend, though we would become engaged later that year – seated together, among new friends who would soon become cherished classmates and colleagues, at the beginning of one of the most impactful years of our lives.

And just as we and our class community finished singing the Shabbat song Lecha Dodi – the very moment in the service where the introductory songs of welcome end, and main part of the Shabbat evening service formally begins – immediately after we finished singing Lecha Dodi, in the quiet lull between that prayer and the next, as the only sound you could hear was the leaves rustling in the warm breeze – suddenly, softly, for the first time that year, we heard the low purring sound of the Shabbat siren: the official public notice, broadcast from towers throughout Jerusalem, letting the city’s inhabitants know that the sun had officially set, and Shabbat had officially begun.

What a wonder: to be in a country that is so attuned to the rhythm of Jewish life, that a soft, soothing siren sounds to let you know that Shabbat has begun.

What a painful contrast to the sirens that blared in Israel this past Shabbat. This past Shabbat, the sirens were not a soft, soothing purr, but rather, a blaring alarm. This past Shabbat, the sirens were not to tell Israelis that Shabbat had begun, but rather, to warn Israelis to take cover. What a stark and devastating contrast.

Like many other people that I’ve spoken to, including many people here in the congregation this evening – over the past several days, I’ve had trouble peeling myself away from the news. On Saturday, I was glued to immediate reporting about the crisis: what had happened, where, how many people had been killed, injured, and abducted. On Sunday and Monday, it was not reporting, but rather, analysis that devoured my attention: how could this have happened, what were the implications for global geopolitics, how was the war-of-public-opinion shaping up on social media?

There were dozens of articles to read, podcasts to listen to, commentators whose opinions I wanted to hear. But at some point on Monday afternoon, it became too much. I was on information overload. I turned off the podcasts, and distracted myself with washing the dishes.

And in that silence – as I was finally able to stop the steady stream of gut-wrenching information and analysis with which I had been willingly bombarding myself for the past two-and-a-half days – at last, the emotional gravity of what we, the Jewish people, had just endured caught up with me, and I collapsed into tears on the kitchen floor.

Over the past four days, each of us may have experienced a variety of feelings. Perhaps we felt sad for the tragic loss of life; angry at the brutality of the perpetrators; worried about our friends and family who live in Israel; confused about where to get reliable information; self-doubting about our level of knowledge of this complicated conflict; hurt by what we’ve seen others post on social media; scared for our own safety, even though we live thousands of miles away from where the fighting in taking place; helpless to do anything, even though all we want to do is help.

These, and likely many other feelings, we bring into our sanctuary tonight, to be held alongside our fellow congregants.

Many of us have heard the painful stories – and maybe even seen the unbearable images and videos – that have emerged over the past four days. Because they are so upsetting, I hesitate to describe them now. Nevertheless, I feel it is my obligation to do – although I hasten to add, I intend to do so without resorting to overly graphic imagery, and without describing what I believe are some of the most upsetting stories and images of the past few days.

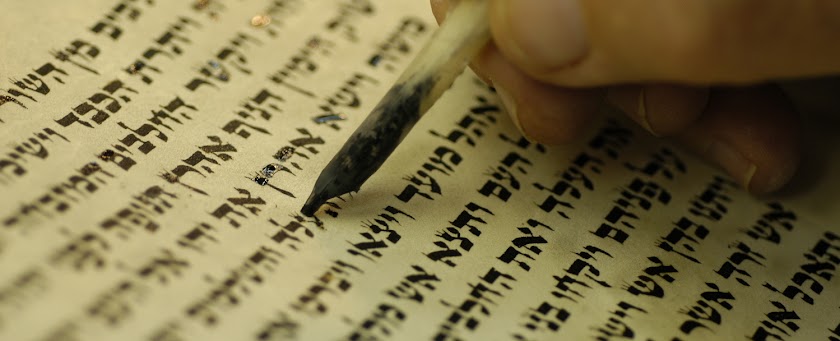

I share these stories and images not out of a sense of voyeurism, but rather, as a part of what we Jews believe is our sacred obligation. We are called upon to bear witness, to raise our voices, in the face of human suffering. As the scholar David Roskies argues – in one of Rabbi Schecter’s most frequently quoted books, The Literature of Destruction – we Jews have a long history of transforming our pain by speaking about it and writing about it: from the ancient biblical Book of Lamentations, to the medieval Jewish poetry composed in the wake of the Crusades, to the memoirs of Holocaust survivors. We Jews are a people who speak our pain aloud.

Perhaps we’ve heard some of these stories. (And again, I intend not to be overly graphic.) The story of 260 young people gunned down at an outdoor music festival. Of dead bodies strewn across the highways. Dozens of people held hostage for twelve hours inside the dining hall at Kibbutz Be’eri. The incredibly upsetting video of a young woman and her partner, as they desperately plead not to be taken, split up by Hamas militants, each loaded onto a separate motorcycle and driven towards Gaza. A Palestinian woman in Gaza – and many others like her – her home destroyed in an airstrike, identifying her sister’s remains in a body bag. Israelis calling their TV and radio stations from the locked safe-rooms of their homes, pleading in a quiet whisper for help. Israeli parents, siblings, and spouses not knowing where their loved ones are, begging the government to help find them – or, devastatingly learning of their fate by seeing their faces on Hamas-posted YouTube videos. All of these haunting images and stories – and many others, much worse, that I will not describe here now.

There are also the much-needed – though significantly fewer and farther between – stories of resilience and hope, stories of human triumph in the face of unbelievable challenges.

For example, the much-circulated

personal story of the journalist Amir Tibon. Tibon lives in a small kibbutz less than 2 miles from the Gaza border. When he and his family heard the sound of rockets, they headed to their safe-room. When it was no just longer the sound of rockets, but also, the sound of machine gun fire from only a few streets away, Tibon made two phone calls – one, to his journalist colleagues to let them know what has happening, and the second, to his mother and father in Tel Aviv. Then, the cell phone service was cut off.

For ten hours, Tibon, his wife, and their two small children, ages one and four, hid in their safe room – trying to keep the kids calm, helping them to understand that they all needed to be completely silent.

Meanwhile, Tibon’s mother and father, retirees in their early sixties, loaded into their car and started driving from Tel Aviv towards the kibbutz. After a long and difficult drive – including an unexpected detour, to help bring a group of injured Israeli soldiers to the hospital – Tibon’s father arrived at the kibbutz.

Suddenly, after ten long hours, Tibon, from the dark of the safe room, heard not only the sound of machine guns, but also, the sound of a gun fire. At last, he thought, the army has come to rescue. A few moments later, a knock on the door. A familiar voice spoke to them in Hebrew. The door opened. And Tibon’s four-year-old daughter exclaimed: sabba higiya! “Grandpa is here.”

Or, perhaps you’ve heard the remarkable story of another

couple in their sixties named David and Rachel: how five Hamas gunmen climbed into their apartment through the bedroom window, and held them hostage there for 15 hours – how Rachel offered them coffee and cookies, how she kept them preoccupied with small talk and conversation, how she bandaged the bleeding hand of one of the wounded militants, until, 15 hours later, their adult son was able to arrive on the scene, provide the security forces with information about the layout of the apartment, and the military broke in through a skylight in the bathroom, rescuing and Rachel and David, alive and unharmed.

Perhaps you’ve heard stories of how quickly

ordinary Israelis around the country have mobilized – in many cases, utilizing the same community-organizing tactics that sustained the pro-democracy protests over the past ten months – to help their fellow citizens who are in harm’s way: opening their homes to displaced people; collecting food, clothing, and household supplies; providing transportation; organizing childcare and hot meals for families whose loved ones have been called up to reserve duty; opening online mental health clinics, to provide professional support through this immense emotional burden; and many other everyday acts of heroism.

And yet, despite these heart-warming stories, for me – and, I imagine, many others in this sanctuary – the main feeling in my heart is pain.

I feel heartbroken – sick to my stomach at the devastating loss of life. It is has been widely commented that this past Saturday was the single deadliest day in Jewish history since the Holocaust. It has been described as the Israeli 9/11, or the Israeli Pearl Harbor. Other commentators have described it as like a pogrom – with Jews mercilessly slaughtered in their own places of residence.

I feel angry. How could Hamas have such little regard for human life? How could they so callously slaughter innocent civilians? How can they possibly believe that it is OK to abduct children and grandmothers, and make them endure public humiliation that I will not here describe?

I feel shocked. How on earth did this happen? How could Israeli military and intelligence forces have been so blindsided by this attack? How could Hamas – who only a few years ago could barely guide a rocket towards its intended target – suddenly have the ability to plan a sophisticated and complex attack, right under the noses of Israel’s vaunted intelligence services?

I feel frightened. I fear for the fate of the more than 150 Israelis who have been taken captive by Hamas. I feel – in only the tiniest fraction of a degree – the unimaginable anxiety that their loved ones must currently be under. Are there relatives alive? What kind of conditions are they being made to endure? In the worst-case scenario, will we ever definitively know what has happened to them? In the best-case scenario – where, God willing, they are returned home alive – how will our lives be forever altered by these unbearable events?

I worry for the Palestinians of Gaza – who are not the same as Hamas, but who will continue to suffer and be killed because of Hamas’s actions. Before this attack, Gaza was already an incredibly difficult place to live. After the attack, the lives of innocent Gazan civilians will be made only worse: with tighter restrictions, and more in the path of violence and danger.

I worry for the 300,000 reservists who have been called to the front lines, and for their families. Will they return home? Where will they find the courage to carry out their mission? When they are faced with moral dilemmas, as they inevitably will be, will their leaders guide them with wisdom?

As I was tucking my kids into bed last night – and again this morning as I said goodbye to them at the bus stop – the obvious occurred to me: why it is that I feel so shaken by these events. I – and, I imagine, many others of us as well – feel so shaken, at least in part, because of how easy it is to imagine ourselves, our kids, and our loved ones in the Israelis’ shoes. For most of us, it is a matter of mere historical accident that our family wound up in the United States, rather than in Israel. It could have just as easily been us in Amir Tibon’s safe room, scared in the dark for 10 hours, praying beyond hope that perhaps sabba higiya, that grandpa might arrive.

But there is another reason why we feel so shaken by these events. As several Israeli commentators have noted, when we ask the question, so common in Israeli society right now, “How could this have happened?” we are not merely asking “Who is to blame?” We are not merely asking “What were the military and intelligence failures that allowed this attack to take place?” We are also saying something much deeper.

When we ask “How could this have happened?” we are also acknowledging how destabilized we, the entire Jewish world, suddenly feels. Israel, which, at least since 1967, has been the symbol of Jewish security and safety; Israel, the country that was established so that the Jewish people could at long last be in control of our own destiny, no long subject to the whims of history; Israel, which is supposed to be a place where Jews around the world who fear for their physical safety can find a refuge and a haven; Israel, the ultimate symbol of our people’s safety suddenly seems far less safe than we realized. It upends our own feeling of safety. It is disorienting, destabilizing, and deeply troubling.

After all, for much of the Jewish people, Israel is more than just a country in the Middle East. It is a symbol, an aspect of who we are, one tile in the mosaic of experiences that comprise our Jewish identity.

Last week, a group of TBS congregants who participate in our Gather initiative met in the sukkah and talked about the metaphor of “home.” For the Jewish people, “home” is one of the most powerful metaphors that we possess. Jewish life doesn’t just take place in the synagogue; equally, it takes place in the home. Our Torah story is one long narrative of our people’s homecoming: from the Land of Israel, down to slavery in Egypt, and back home again. On the level of a human life, we Jews believe that our souls originate from the Source of Life, and that when we die, they return home again. “Home,” God willing, is where we feel safe, where we feel loved, where we can be our truest selves.

The Jewish people has many homes. The actual, physical houses and apartments in which we live. The old neighborhood in which we grew up. The countries all around the diaspora of which we are citizens. The synagogues in which we feel grounded.

And also, for many among the Jewish people, Israel is also some kind of a home. Even if we do not live there, many of us might feel a deep connection to the place, feel a sense of responsibility for what happens there, feel a deep sense of pride when the news is good, feel a deep sense of pain when the news is heartbreaking.

This weekend, one of our homes was attacked. And along with it, many of us might feel that our own safety has been attacked, that our sense of self has been attacked, that our Jewishness has been attacked.

But it is precisely when our home is attacked, more than ever, that we need to remember that “home” is about so much more than just a physical place. On a very deep level, home is about also about family.

And so we come together tonight as a family – with our immediate family, our spouses, children, parents, siblings, and grandparents; we come together with our extended congregational family, the people with whom we share lifes joys and sorrows; we come together with our global Jewish family, the people around the world with whom we share a common history and heritage, and feel sense of kinship with, even though we’ve never met.

When our home is attacked, we do the only thing we can do: we open our arms up wide, and wrap them around our family.