I grew up in a family that loved movie musicals. [1] The rack of VHS tapes underneath our television was stocked with all the classics: West Side Story, Singin’ in the Rain, Oklahoma! You name it, we’d seen it.

But there was one musical that, although I had many opportunities to see it as a kid, I always backed away from: Andrew Lloyd Webber’s rock-opera Jesus Christ Superstar. Growing up in Tallahassee, Florida, on the edge of the bible belt, I felt no need to watch a musical about Jesus. I felt myself sufficiently surrounded by Christian religious influences. I did not feel the need to seek out more in my spare time.

And so it was somewhat begrudgingly this past Sunday evening that I tuned in to watch NBC’s live broadcast of the musical. And I have to say that, despite my hesitations, I really, really enjoyed it.

The musical tells the story of the final days of Jesus’s life: the last supper, Jesus’s arrest, his trial, and eventual crucifixion. Bible scholars refer to this story as “the passion narrative” -- where the word “passion” is used in its original Latin sense, meaning “suffering.” It is the story of Jesus’s suffering. But unlike most versions of that story, the musical is told not from the perspective of Jesus, but rather from the perspective of Judas -- the disciple who, according to Christian scriptures, betrays Jesus by turning him over to the authorities.

Through Judas’s eyes, we see a different version of the story than we may be used to. We see Jesus not only as a charismatic preacher who loves the downtrodden, but also, as the title of the musical suggests, as a “superstar” -- a pop-culture phenom, who quickly gets carried away by his own rising fame. Through Judas’s eyes, Jesus looks like a rockstar who is thrilled with all of his positive publicity and is veering dangerously close to believing all the hype about himself -- that he may in fact be the son of God. [2] In this context, the 12 disciples become his groupies, more interested in riding Jesus’s coattails than in healing the sick. [3] As Jesus’s popularity grows, so too do the threats against his life. And so Judas decides to turn his beloved teacher in -- with hopes that Jesus’s teachings, rather than his stardom, will live on.

In this way, the musical is like a familiar genre of Jewish literature -- the genre of midrash, in which events from the Bible are retold from a contemporary perspective in order to provide them with new layers of meaning. Jesus Christ Superstar is a modern Christian midrash -- and in my view, a powerful one.

And yet, watching the musical along with nine-and-a-half million other Americans this past Easter Sunday, I felt, at many points, uneasy. Because even when it is told from the perspective of Judas, the passion narrative presents what is, at best, an unflattering view of those Jews who did not follow Jesus. At worst, it flatly condemns those Jews for Jesus’s death. Consider the following narrative details that originate in the New Testament and find their way into the musical. We see Caiaphas, the Jewish High Priest, plotting for Jesus’s capture; the Sanhedrin, an ancient Jewish court, decreeing that Jesus is guilty; a riotous Jewish mob demanding that Jesus be crucified; and of course, there’s the villain himself -- Judas, the betrayer, whose very name could not be any more evocative of the Jewish people he’s made to represent.

For centuries, passion plays performed on Easter Sunday inflamed Europe’s Christian masses against their Jewish neighbors. Hitler famously described one particularly brutal passion play as “history’s most convincing portrayal of the menace of the Jew.” And although, in 1965, the Catholic Church issued a formal proclamation stating the Jews could no longer be blamed as Christ-killers, the epithet has continued to stick. Perhaps you remember Mel Gibson’s 2004 movie The Passion of the Christ -- and the controversy over whether the film carried a blatantly anti-Jewish message.

Consequently, mine was not the first set of eyebrows to raise over the possible anti-Jewish undertones of Jesus Christ Superstar. When the musical was first made into a film in 1973, it was sharply criticized by both the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee. Despite its sympathetic portrayal of Judas, the musical is seemingly inexorably yoked to the anti-Jewish heritage of the Christian scriptures.

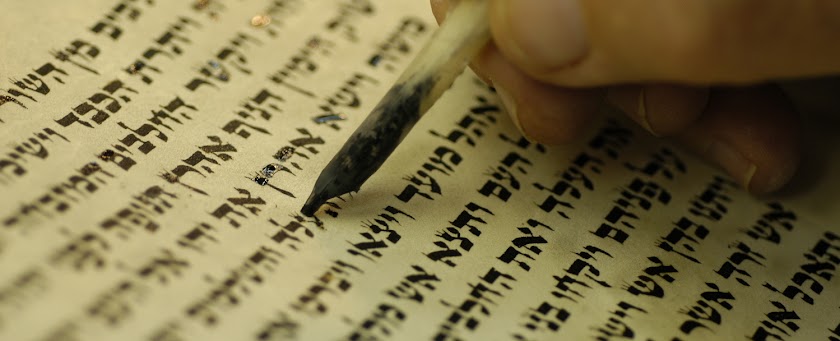

We cannot seek to rewrite the Bible. We can, however, seek to better understand the Bible, by exploring the historical circumstances in which it was written. We Jews are accustomed doing this with our own tradition -- reading the Hebrew Bible with a critical eye, employing the best of contemporary scholarship to help uncover the possible motives of the people who wrote it. [4] We do this not to pick our tradition apart, or to devoid our people’s stories of their transformative power. Rather, we bring this critical lens to our biblical scholarship in order to add yet another layer of depth and understanding to the text we hold so dear. Especially in places where that text has been used not as a tool for spiritual elevation, but rather, as a bludgeon for denying the humanity of another human being, our scholarly lens is critically important.

I like Jesus Christ Superstar -- as a musical, and as an ingenious work of modern Christian midrash. But if we are to love the show even despite its anti-Jewish undertones, then we had better bring our critical lens to the text that informs it. We had better understand the Christian scriptures and the world that created them. [5]

First, let us understand that, although the New Testament tells stories from the life of Jesus, those stories were not written down until many decades after Jesus died.

Second, and perhaps more important, Christian scripture, like the Hebrew Bible, is not one book, but rather is a collection of books that are all on the same topic. It is like a library -- with a variety of books, composed by a variety of authors, writing in a variety of different times and places. As is the case in a library, some of these authors drew upon each other’s work. Other authors unwittingly contradicted each other’s work. Thus, when we talk about “the passion narrative,” we are not talking about a single story told sequentially in a single volume, but rather, about a patchwork of disparate stories sewn together over time.

If we carefully take apart the stitching, we can trace how different versions of the same story evolved and changed over time. For a helpful example, let’s follow one story that is central to the musical Jesus Christ Superstar. Let’s trace the evolution of the stories about the Last Supper and Judas’s betrayal of Jesus.

The earliest stratum of the New Testament is the letters of Paul -- written around the year 50 of the Common Era. In these letters, the Last Supper is described, but the detail about a betrayal is conspicuously absent. [6] What’s more, not once in all of Paul’s letters is the name Judas even mentioned. It seems that in the 50s of the Common Era, the story of Judas’s betrayal did not yet exist.

But just a few short decades later, all of that would change. The next-written statum of the New Testament is the Gospel of Mark, written around the year 72 CE. This book not only mentions a betrayal, it ascribes that betrayal to Judas. [7] In still the next stratum of the New Testament, the story takes on even greater detail. The Gospel of Matthew [8] picks up where Mark had left off -- and adds that Judas, recognizing his guilt, decides to take his own life.

Using our critical lens, we see that there is no one story of Judas at the Last Supper. Rather, there is a patchwork of stories that evolved over time, one building upon another, which were eventually sewn together into what we now call the Christian scriptures.

But we ought to wonder: what happened in those critical decades between the writing of the first stratum and the second? What happened that caused Mark to write a story about Judas’s betrayal when Paul, only twenty years earlier, had seemingly never heard of such a story? To answer this question, we need to understand the historical context in which the New Testament was written.

In the year 64 CE, a disastrous fire tore through the city of Rome. Perhaps you’ve heard the charge that the emperor, Nero, fiddled while Rome burned. That charge is debatable. But what we can verify [9] is that Nero blamed the fire on the Rome’s burgeoning Christian community. Nero captured and killed Christians by the hundreds. Those that he didn’t kill, he tortured, and compelled them to turn in their fellow Christians who were in hiding. These events rocked the early Christian community, imperiling their safety throughout the Roman empire.

Meanwhile, only two years later, in 66 CE, a Jewish revolt against Roman rule broke out in Jerusalem. Rome bit back, and hard. And although the early Christians were not centrally involved in the revolt, they keenly felt its impact. Early Christians grew wary of being too closely associated with their rebelling Jewish neighbors -- with whom they shared a homeland, a religious tradition, and in many cases, family ties.

These events in the 60s of the Common Era -- Nero’s fire in Rome, and the Jewish revolt in Jerusalem -- destabilized the early Christian community. Naturally, they sought to ingratiate themselves to Rome and distance themselves from the Jewish rebels. What’s more, to buoy their strengths, early Christians needed a model for how a righteous person would respond to betrayal by a friend, as many of them were being betrayed by their friends unto Nero.

To address these needs, early Christians looked for inspiration to the book that they held sacred -- the Hebrew Bible. [10] They found there, in the Book of Genesis, the story of a group of twelve confidants, in which one of the twelve sold out another -- the story of Joseph and his brother Judah. [11] It was a perfect fit. The story of Joseph and Judah evolved into the story of Jesus and Judas.

The character of Judas quickly became the early Christians’ tool for distancing themselves from the Jewish rebels and ingratiating themselves with Rome. Other examples [12] would be built upon it, but the character of Judas would remain the symbol par excellence of the New Testament’s anti-Jewish sentiment.

And it is for precisely this reason that I love the musical Jesus Christ Superstar so much. Because, although the show may be prone to many of the New Testament’s regular anti-Jewish themes, the show also does something unique. It gives Judas a fair chance -- a chance to tell his side of the story.

As Jews, we, too, need to understand Judas’s side of the story -- not by writing a musical about him, but rather, by learning as much as we can about the Christian scriptures and the world that shaped them.

If I could, I would tell a younger version of myself not to back away from watching Jesus Christ Superstar, but rather, to lean in and learn as much about the story as possible. If I could, I would tell that younger version of myself that it is only by understanding the world that shaped the Bible that we can come to understand the world that the Bible has shaped.

------

[1] The title of this sermon refers to a non-canonical (Coptic) book -- pseudonymously ascribed to Judas, which is possibly dateable to the 2nd/3rd century CE -- entitled The Gospel of Judas. That book contains imagined conversations between Judas and Jesus, in which Jesus instructs Judas to turn him over to the authorities. The Gospel of Judas was published in English, with great fanfare, in 2006.

[2] See, for example, the lyrics to the show’s opening song, “Heaven on Their Minds,” sung by Judas: “You've started to believe / The things they say of you. / You really do believe / This talk of God is true. / And all the good you've done / Will soon get swept away. / You've begun to matter more / Than the things you say.”

[3] See, for example, the lyrics (which, to my eye, are intended to be understood as haughty) to “The Last Supper,” sung by the Apostles: “Always hoped that I'd be an apostle. / Knew that I would make it if I tried. / Then when we retire, we can write the Gospels, / So they'll still talk about us when we've died.”

[4] This method of biblical scholarship is broadly referred to as “source criticism.” For a crash course, see: Friedman, Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? San Francisco: Harper One, 1997.

[5] In this effort, I am deeply indebted to my teacher, Rabbi Michael Cook, Ph.D. Much of the research that follows is based on his book: Modern Jews Engage the New Testament: Enhancing Jewish Well-Being in a Christian Context. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2008.

[6] See I Corinthians 11:23. Cook and others (The Jewish Annotated New Testament, Oxford University Press) argue that the word in that verse that is often translated as “betrayed” would be better translated as “handed over [unto death].”

[7] Mark 14:43

[8] Written circa 85 CE. See Matthew 27:3ff.

[9] Tacitus, Annals, xv.44

[10] The traditional Christian argument would be that the events in the Hebrew Bible predicted the events of Jesus’s life. A source-critical eye recognizes that it is far more likely that Christian scriptures borrowed motifs from the Hebrew Bible (just as the Hebrew Bible borrowed from its antecedent sources).

[11] See Genesis 37:26. The parallels continue. Judah, like Judas, betrays his brother/confidant: (1) at a meal, and (2) in exchange for a small sum of silver.

[12] For example: the Sanhedrin trial and the Barabbas episode. For a detailed discussion, see Cook, chs. 11-12.

But there was one musical that, although I had many opportunities to see it as a kid, I always backed away from: Andrew Lloyd Webber’s rock-opera Jesus Christ Superstar. Growing up in Tallahassee, Florida, on the edge of the bible belt, I felt no need to watch a musical about Jesus. I felt myself sufficiently surrounded by Christian religious influences. I did not feel the need to seek out more in my spare time.

And so it was somewhat begrudgingly this past Sunday evening that I tuned in to watch NBC’s live broadcast of the musical. And I have to say that, despite my hesitations, I really, really enjoyed it.

The musical tells the story of the final days of Jesus’s life: the last supper, Jesus’s arrest, his trial, and eventual crucifixion. Bible scholars refer to this story as “the passion narrative” -- where the word “passion” is used in its original Latin sense, meaning “suffering.” It is the story of Jesus’s suffering. But unlike most versions of that story, the musical is told not from the perspective of Jesus, but rather from the perspective of Judas -- the disciple who, according to Christian scriptures, betrays Jesus by turning him over to the authorities.

Through Judas’s eyes, we see a different version of the story than we may be used to. We see Jesus not only as a charismatic preacher who loves the downtrodden, but also, as the title of the musical suggests, as a “superstar” -- a pop-culture phenom, who quickly gets carried away by his own rising fame. Through Judas’s eyes, Jesus looks like a rockstar who is thrilled with all of his positive publicity and is veering dangerously close to believing all the hype about himself -- that he may in fact be the son of God. [2] In this context, the 12 disciples become his groupies, more interested in riding Jesus’s coattails than in healing the sick. [3] As Jesus’s popularity grows, so too do the threats against his life. And so Judas decides to turn his beloved teacher in -- with hopes that Jesus’s teachings, rather than his stardom, will live on.

In this way, the musical is like a familiar genre of Jewish literature -- the genre of midrash, in which events from the Bible are retold from a contemporary perspective in order to provide them with new layers of meaning. Jesus Christ Superstar is a modern Christian midrash -- and in my view, a powerful one.

And yet, watching the musical along with nine-and-a-half million other Americans this past Easter Sunday, I felt, at many points, uneasy. Because even when it is told from the perspective of Judas, the passion narrative presents what is, at best, an unflattering view of those Jews who did not follow Jesus. At worst, it flatly condemns those Jews for Jesus’s death. Consider the following narrative details that originate in the New Testament and find their way into the musical. We see Caiaphas, the Jewish High Priest, plotting for Jesus’s capture; the Sanhedrin, an ancient Jewish court, decreeing that Jesus is guilty; a riotous Jewish mob demanding that Jesus be crucified; and of course, there’s the villain himself -- Judas, the betrayer, whose very name could not be any more evocative of the Jewish people he’s made to represent.

For centuries, passion plays performed on Easter Sunday inflamed Europe’s Christian masses against their Jewish neighbors. Hitler famously described one particularly brutal passion play as “history’s most convincing portrayal of the menace of the Jew.” And although, in 1965, the Catholic Church issued a formal proclamation stating the Jews could no longer be blamed as Christ-killers, the epithet has continued to stick. Perhaps you remember Mel Gibson’s 2004 movie The Passion of the Christ -- and the controversy over whether the film carried a blatantly anti-Jewish message.

Consequently, mine was not the first set of eyebrows to raise over the possible anti-Jewish undertones of Jesus Christ Superstar. When the musical was first made into a film in 1973, it was sharply criticized by both the Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Committee. Despite its sympathetic portrayal of Judas, the musical is seemingly inexorably yoked to the anti-Jewish heritage of the Christian scriptures.

We cannot seek to rewrite the Bible. We can, however, seek to better understand the Bible, by exploring the historical circumstances in which it was written. We Jews are accustomed doing this with our own tradition -- reading the Hebrew Bible with a critical eye, employing the best of contemporary scholarship to help uncover the possible motives of the people who wrote it. [4] We do this not to pick our tradition apart, or to devoid our people’s stories of their transformative power. Rather, we bring this critical lens to our biblical scholarship in order to add yet another layer of depth and understanding to the text we hold so dear. Especially in places where that text has been used not as a tool for spiritual elevation, but rather, as a bludgeon for denying the humanity of another human being, our scholarly lens is critically important.

I like Jesus Christ Superstar -- as a musical, and as an ingenious work of modern Christian midrash. But if we are to love the show even despite its anti-Jewish undertones, then we had better bring our critical lens to the text that informs it. We had better understand the Christian scriptures and the world that created them. [5]

First, let us understand that, although the New Testament tells stories from the life of Jesus, those stories were not written down until many decades after Jesus died.

Second, and perhaps more important, Christian scripture, like the Hebrew Bible, is not one book, but rather is a collection of books that are all on the same topic. It is like a library -- with a variety of books, composed by a variety of authors, writing in a variety of different times and places. As is the case in a library, some of these authors drew upon each other’s work. Other authors unwittingly contradicted each other’s work. Thus, when we talk about “the passion narrative,” we are not talking about a single story told sequentially in a single volume, but rather, about a patchwork of disparate stories sewn together over time.

If we carefully take apart the stitching, we can trace how different versions of the same story evolved and changed over time. For a helpful example, let’s follow one story that is central to the musical Jesus Christ Superstar. Let’s trace the evolution of the stories about the Last Supper and Judas’s betrayal of Jesus.

The earliest stratum of the New Testament is the letters of Paul -- written around the year 50 of the Common Era. In these letters, the Last Supper is described, but the detail about a betrayal is conspicuously absent. [6] What’s more, not once in all of Paul’s letters is the name Judas even mentioned. It seems that in the 50s of the Common Era, the story of Judas’s betrayal did not yet exist.

But just a few short decades later, all of that would change. The next-written statum of the New Testament is the Gospel of Mark, written around the year 72 CE. This book not only mentions a betrayal, it ascribes that betrayal to Judas. [7] In still the next stratum of the New Testament, the story takes on even greater detail. The Gospel of Matthew [8] picks up where Mark had left off -- and adds that Judas, recognizing his guilt, decides to take his own life.

Using our critical lens, we see that there is no one story of Judas at the Last Supper. Rather, there is a patchwork of stories that evolved over time, one building upon another, which were eventually sewn together into what we now call the Christian scriptures.

But we ought to wonder: what happened in those critical decades between the writing of the first stratum and the second? What happened that caused Mark to write a story about Judas’s betrayal when Paul, only twenty years earlier, had seemingly never heard of such a story? To answer this question, we need to understand the historical context in which the New Testament was written.

In the year 64 CE, a disastrous fire tore through the city of Rome. Perhaps you’ve heard the charge that the emperor, Nero, fiddled while Rome burned. That charge is debatable. But what we can verify [9] is that Nero blamed the fire on the Rome’s burgeoning Christian community. Nero captured and killed Christians by the hundreds. Those that he didn’t kill, he tortured, and compelled them to turn in their fellow Christians who were in hiding. These events rocked the early Christian community, imperiling their safety throughout the Roman empire.

Meanwhile, only two years later, in 66 CE, a Jewish revolt against Roman rule broke out in Jerusalem. Rome bit back, and hard. And although the early Christians were not centrally involved in the revolt, they keenly felt its impact. Early Christians grew wary of being too closely associated with their rebelling Jewish neighbors -- with whom they shared a homeland, a religious tradition, and in many cases, family ties.

These events in the 60s of the Common Era -- Nero’s fire in Rome, and the Jewish revolt in Jerusalem -- destabilized the early Christian community. Naturally, they sought to ingratiate themselves to Rome and distance themselves from the Jewish rebels. What’s more, to buoy their strengths, early Christians needed a model for how a righteous person would respond to betrayal by a friend, as many of them were being betrayed by their friends unto Nero.

To address these needs, early Christians looked for inspiration to the book that they held sacred -- the Hebrew Bible. [10] They found there, in the Book of Genesis, the story of a group of twelve confidants, in which one of the twelve sold out another -- the story of Joseph and his brother Judah. [11] It was a perfect fit. The story of Joseph and Judah evolved into the story of Jesus and Judas.

The character of Judas quickly became the early Christians’ tool for distancing themselves from the Jewish rebels and ingratiating themselves with Rome. Other examples [12] would be built upon it, but the character of Judas would remain the symbol par excellence of the New Testament’s anti-Jewish sentiment.

And it is for precisely this reason that I love the musical Jesus Christ Superstar so much. Because, although the show may be prone to many of the New Testament’s regular anti-Jewish themes, the show also does something unique. It gives Judas a fair chance -- a chance to tell his side of the story.

As Jews, we, too, need to understand Judas’s side of the story -- not by writing a musical about him, but rather, by learning as much as we can about the Christian scriptures and the world that shaped them.

If I could, I would tell a younger version of myself not to back away from watching Jesus Christ Superstar, but rather, to lean in and learn as much about the story as possible. If I could, I would tell that younger version of myself that it is only by understanding the world that shaped the Bible that we can come to understand the world that the Bible has shaped.

------

[1] The title of this sermon refers to a non-canonical (Coptic) book -- pseudonymously ascribed to Judas, which is possibly dateable to the 2nd/3rd century CE -- entitled The Gospel of Judas. That book contains imagined conversations between Judas and Jesus, in which Jesus instructs Judas to turn him over to the authorities. The Gospel of Judas was published in English, with great fanfare, in 2006.

[2] See, for example, the lyrics to the show’s opening song, “Heaven on Their Minds,” sung by Judas: “You've started to believe / The things they say of you. / You really do believe / This talk of God is true. / And all the good you've done / Will soon get swept away. / You've begun to matter more / Than the things you say.”

[3] See, for example, the lyrics (which, to my eye, are intended to be understood as haughty) to “The Last Supper,” sung by the Apostles: “Always hoped that I'd be an apostle. / Knew that I would make it if I tried. / Then when we retire, we can write the Gospels, / So they'll still talk about us when we've died.”

[4] This method of biblical scholarship is broadly referred to as “source criticism.” For a crash course, see: Friedman, Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? San Francisco: Harper One, 1997.

[5] In this effort, I am deeply indebted to my teacher, Rabbi Michael Cook, Ph.D. Much of the research that follows is based on his book: Modern Jews Engage the New Testament: Enhancing Jewish Well-Being in a Christian Context. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2008.

[6] See I Corinthians 11:23. Cook and others (The Jewish Annotated New Testament, Oxford University Press) argue that the word in that verse that is often translated as “betrayed” would be better translated as “handed over [unto death].”

[7] Mark 14:43

[8] Written circa 85 CE. See Matthew 27:3ff.

[9] Tacitus, Annals, xv.44

[10] The traditional Christian argument would be that the events in the Hebrew Bible predicted the events of Jesus’s life. A source-critical eye recognizes that it is far more likely that Christian scriptures borrowed motifs from the Hebrew Bible (just as the Hebrew Bible borrowed from its antecedent sources).

[11] See Genesis 37:26. The parallels continue. Judah, like Judas, betrays his brother/confidant: (1) at a meal, and (2) in exchange for a small sum of silver.

[12] For example: the Sanhedrin trial and the Barabbas episode. For a detailed discussion, see Cook, chs. 11-12.