Westchester Reform Temple | Scarsdale, NY

Yom Kippur Afternoon 5778

I have a vivid memory of Ms. Burton -- the teacher at my elementary school who supervised the cafeteria at lunchtime. I am taking my Styrofoam lunch tray -- half-full of green beans and a partially eaten baked potato -- to the garbage. Ms. Burton stops me on the way. “I see that someone is giving up their membership to the clean plate club,” she says. I never knew I had been a member in the first place. “You know,” she continues, “there are children right here in this school who don’t have enough to eat.” I didn’t know that. But I shrug it off as I dump the Styrofoam tray into the garbage, skeptical that if I finished my baked potato, those hungry children would somehow be less hungry.

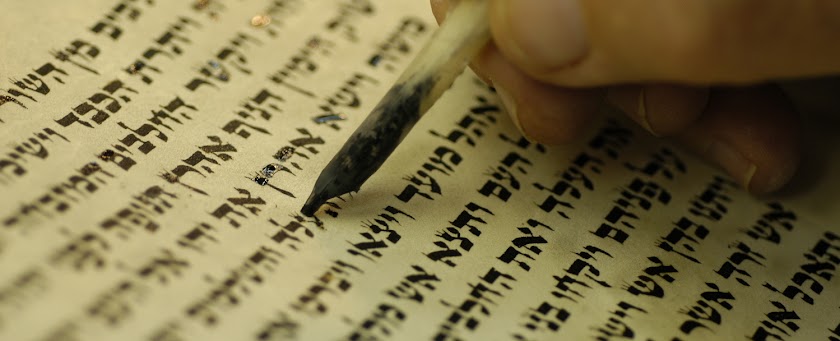

This afternoon’s Torah portion teaches that, despite my childhood doubts, Ms. Burton was right. There is a value in belonging to the clean plate club. But the Torah’s message is slightly more nuanced than Ms. Burton’s. Our Torah portion reads: “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap all way to the corners of your field. You shall leave the corners of your field for the poor and for the stranger” (Leviticus 19:9-10). Where Ms. Burton said “eat all that you take,” the Torah says “take only what you need.”

Our Torah portion is concerned with the equitable distribution of food -- as much a problem today as it was 2,500 years ago. Today, the world produces enough food to feed the entire planet one-and-a-half times over. And yet, 800 million people -- one out of every ten -- go hungry every day. On Yom Kippur, WRT responds to this problem by committing to restock the Food Bank of Westchester with 10,000 pounds of non-perishable goods. But even then, Jewish tradition impels us to ask if we have done enough. There is an entire tractate of the Mishnah -- an entire field of study in Jewish law -- devoted to this question. The Mishnah notices an ambiguity in this afternoon’s Torah reading: sure, we should leave the corner of our field for the poor, but how big is a corner? How do we know that we’ve done our part?

But the problem is deeper still. All of our food waste takes not only a human toll, but an environmental toll. On the production end, over-farming erodes the soil, wastes water, and destroys natural habitats. On the consumer end, food waste that lies rotting in landfills produces 20% of the world’s greenhouse gas.

We can be proud that WRT is engaged in addressing this problem. Our Zero Waste initiative ensures that all leftover food scraps are composted, rather than dumped. And we’ve taken hold of a new definition of the clean plate club, by eschewing all paper and Styrofoam products -- like the one from my elementary school cafeteria -- and instead using only compostables. Our Zero Waste initiative, established and led by congregants Ron Schulhof and Michelle Sterling, has become the preeminent model of sustainability in our area -- setting the example for other houses of worship, for local schools, and for the Scarsdale Village food-scraps program. In fact, Ron and Michelle, along with Rabbi Blake, will be presenting at the upcoming URJ Biennial -- the central gathering of 5,000 Reform Jews this December in Boston -- on how WRT became a Zero Waste synagogue, and what other Jewish communities can learn from our best practices.

We should be proud of all these achievements. And if you don’t yet participate in the Scarsdale food scraps program, it’s never too late to start. After all, this work is never finished. We must every day recommit ourselves to pursuing food justice and sustainable agriculture -- to leaving the corners of our field for the poor. Because when our tradition asks, “How big is a corner?” the answer comes back in no uncertain terms. Ein lahem shiur, it says. “There is no size limit.” Give as much as you can. Take only what you need. Or, as Ms. Burton would put it, “Don’t throw away that Styrofoam plate. Strive, in all ways, to be a member of the clean plate club.”

Yom Kippur Afternoon 5778

I have a vivid memory of Ms. Burton -- the teacher at my elementary school who supervised the cafeteria at lunchtime. I am taking my Styrofoam lunch tray -- half-full of green beans and a partially eaten baked potato -- to the garbage. Ms. Burton stops me on the way. “I see that someone is giving up their membership to the clean plate club,” she says. I never knew I had been a member in the first place. “You know,” she continues, “there are children right here in this school who don’t have enough to eat.” I didn’t know that. But I shrug it off as I dump the Styrofoam tray into the garbage, skeptical that if I finished my baked potato, those hungry children would somehow be less hungry.

This afternoon’s Torah portion teaches that, despite my childhood doubts, Ms. Burton was right. There is a value in belonging to the clean plate club. But the Torah’s message is slightly more nuanced than Ms. Burton’s. Our Torah portion reads: “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap all way to the corners of your field. You shall leave the corners of your field for the poor and for the stranger” (Leviticus 19:9-10). Where Ms. Burton said “eat all that you take,” the Torah says “take only what you need.”

Our Torah portion is concerned with the equitable distribution of food -- as much a problem today as it was 2,500 years ago. Today, the world produces enough food to feed the entire planet one-and-a-half times over. And yet, 800 million people -- one out of every ten -- go hungry every day. On Yom Kippur, WRT responds to this problem by committing to restock the Food Bank of Westchester with 10,000 pounds of non-perishable goods. But even then, Jewish tradition impels us to ask if we have done enough. There is an entire tractate of the Mishnah -- an entire field of study in Jewish law -- devoted to this question. The Mishnah notices an ambiguity in this afternoon’s Torah reading: sure, we should leave the corner of our field for the poor, but how big is a corner? How do we know that we’ve done our part?

But the problem is deeper still. All of our food waste takes not only a human toll, but an environmental toll. On the production end, over-farming erodes the soil, wastes water, and destroys natural habitats. On the consumer end, food waste that lies rotting in landfills produces 20% of the world’s greenhouse gas.

We can be proud that WRT is engaged in addressing this problem. Our Zero Waste initiative ensures that all leftover food scraps are composted, rather than dumped. And we’ve taken hold of a new definition of the clean plate club, by eschewing all paper and Styrofoam products -- like the one from my elementary school cafeteria -- and instead using only compostables. Our Zero Waste initiative, established and led by congregants Ron Schulhof and Michelle Sterling, has become the preeminent model of sustainability in our area -- setting the example for other houses of worship, for local schools, and for the Scarsdale Village food-scraps program. In fact, Ron and Michelle, along with Rabbi Blake, will be presenting at the upcoming URJ Biennial -- the central gathering of 5,000 Reform Jews this December in Boston -- on how WRT became a Zero Waste synagogue, and what other Jewish communities can learn from our best practices.

We should be proud of all these achievements. And if you don’t yet participate in the Scarsdale food scraps program, it’s never too late to start. After all, this work is never finished. We must every day recommit ourselves to pursuing food justice and sustainable agriculture -- to leaving the corners of our field for the poor. Because when our tradition asks, “How big is a corner?” the answer comes back in no uncertain terms. Ein lahem shiur, it says. “There is no size limit.” Give as much as you can. Take only what you need. Or, as Ms. Burton would put it, “Don’t throw away that Styrofoam plate. Strive, in all ways, to be a member of the clean plate club.”