I grew up in Tallahassee, FL, the panhandle, on the edge of the Bible Belt. Out of my high school graduating class of 450 students, I was one of only four Jews. Every day before school began, a student group called the Fellowship of Christian Athletes would gather around the flag pole for a morning prayer circle -- a ritual that, to me, seemed to signal that was America and democracy were rightfully under the domain of two identity groups: Christians, and athletes -- of which, I was a part of neither.

It was in this cultural context that my complicated relationship with Christmas grew. If our family went to the mall in December, the stores were all decorated with the wreaths and glittering lights, a girl scout troop was selling poinsettias, dozens of children lined up to have their picture taken with Santa, and my own youth theatre company had been invited to stand in the mall’s main concourse and sing a repertoire of Christmas songs -- wishing the crowds of shoppers first “a merry little Christmas,” and then, “a holly jolly” one. In December, the mall was transformed from an ordinary center of retail commerce into a magical winter wonderland, evidence that Christmas was indeed “the most wonderful time of year” -- but none of it was meant for me.

Predictably, these childhood experiences led me to identify with the Grinch Who Stole Christmas or Ebernezer Scrooge. I’ve even been known to consciously choose not to wear red or green in the month of December, so as to avoid inadvertently reinforcing the idea that those are the colors of the season. But unlike Scrooge or the Grinch, it was not that I despised joy and wanted to keep others from feeling it as well. Mine was no mere “bah humbug.” Rather, my resistance to Christmas arose from my surrounding cultural context. Similar to how I felt as I watched the Fellowship of Christian Athletes gather around the flagpole every morning, Christmas reminded me that, as a Jew in Tallahassee, I would always be a cultural outsider.

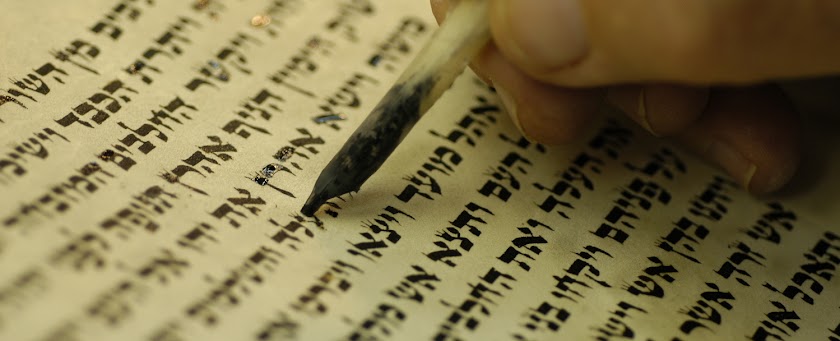

Of course, I’m not the first person in Jewish history to have a complicated relationship with Christmas. The challenge goes back thousands of years, all the way to the Rabbis of the Talmud. [1] The ancient Rabbis were evidently very familiar with what we now know as the Christmas story -- the story of Jesus’s birth, as recorded in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. [2]

The Rabbis not only knew these stories, they were also seemingly uncomfortable about the theological claims that those stories make. The ancient Rabbis took what they knew of the Christmas narrative and crafted their own version of the story -- a counter-narrative, a theological rebuttal, which is recorded in the Talmud. [3]

As we might expect, these counter-narratives are highly polemical and more than a little bit unflattering. Where the Gospels report that Mary conceived by way of the Holy Spirit, the Talmudic counter-narratives suggest that Mary conceived by way of extra-marital affair. Where the Gospels report that Jesus’s parents had to flee to Egypt with their newborn son, the Talmudic counter-narratives suggest that while in Egypt, Jesus became an apprentice of the Pharaoh’s magicians -- and that the so-called miracles of Jesus’s ministry were in fact nothing more than Egyptian sorcery.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the ancient Rabbis’ discomfort with Christmas looks different from my own. After all, the Rabbis were living in a time in which Judaism and Christianity were actively competing to show which tradition had better theological insight. It makes sense that the Rabbis are concerned with the theological implications of the Christmas story -- wrestling not with the ubiquity of Christmas culture, as I did in my adolescence, but rather, wrestling with what it means for a religion to claim that its inspirational figure is the child of God.

In our time, the theological dimensions of American Christmas have significantly faded. This trend goes back to the Puritans, who, despite their religious fervor, disliked the holiday of Christmas. They objected to the feasting, drinking, and other rowdy behaviors that so often accompanied the holiday -- and in an effort to curb those behaviors, the Puritans made the celebration of Christmas illegal.

And while the legal prohibition against the holiday was eventually lifted, their Puritans’ attitude towards Christmas would hold sway for many centuries -- with public institutions, including schools, and even the United States Congress, open for business on Christmas Day all the way through the mid-1800s. But while the Puritans backed away from celebrating Christmas, other, non-religious cultural influences came forward to fill the void -- moving the holiday’s focus from the Church to the home, from the figure of Jesus to the figure of Santa, and, in time, to the holiday’s commercialization, and, some would argue, full secularization.

Even the US Supreme Court has weighed in on Christmas’s secular status. In a 1989 case known as Allegheny County v. the ACLU, our nation’s highest court declared that while a nativity scene on government property violated the constitutional right to freedom of religion, a Christmas tree on government property did not -- with the majority arguing that the symbol of the Christmas tree has “attained secular status in our society.” [4]

It makes sense, therefore, that the American Jewish response to Christmas has not been theological, as was the case with the Rabbis of the Talmud, but rather, has been cultural. If December in America is marked by Christmas songs on the radio and Christmas movies on TV, American Jews have responded with our own cultural creations: from the Daveed Diggs song “Puppy for Chanukkah” to the movie The Hebrew Hammer. If the Christmas table is set with eggnog and a honey-baked ham, American Jews have responded with our own culinary tradition: Chinese food and a movie -- a cultural custom that, according to some sociologists of American Jewry, [5] has become as widespread as many of our most sacred religious rituals.

I suspect that I will always feel some of my childhood discomfort about Christmas -- the feeling of being a cultural outsider. Deeply ingrained experiences stay with us for a long time.

But of course, I’ve also grown since then. I feel more self-assured of who I am as a Jew, and what it is that I believe. Surprisingly, while I still feel myself to be an outsider to Christmas culture, I find myself intrigued by Christmas theology. I don’t feel threatened by it. Theology, after all, is not the main axis along which Christmas in America expressed. What’s more, as my own theological commitments have matured, I find that I’m better able to appreciate other religious traditions without feeling like my own is being threatened. I find that I’m able to get something meaningful out of interfaith dialogue, and not just that old childhood feeling that my Jewishness somehow makes me an outsider.

A mentor of mine compares interfaith dialogue to the experience of going to an art museum. [6] In one room are the Impressionists. In another room, the Cubists. Each of them has their own style, their own way of depicting the world. The Impressionists might paint a flower one way, and the Cubists, an entirely different way. Neither style negates the power and beauty of the other. Each has its own unique and perfectly valid window on the world. And sometimes, the artistic vision of the Cubists might even inspire and enhance the artistic vision of the Impressionists.

The same is true of interfaith dialogue. When my Christian friends and colleagues say that Christmas celebrates the birth of the son of God, I can come to appreciate the power and beauty of that idea without it negating my own theological commitments. If I’m open to it, I might even find myself inspired by that idea -- and work to translate that theological insight into my own religious idiom.

What, then, might we, as Jews, learn from the theology of the Christmas story? How might we translate this holiday’s central theological idea -- the birth of the son of God -- into a theological idiom that we, as Jews, can appreciate?

We might say it like this: the divine can be embodied. [7] The ideals that we ascribe to God -- like truth, compassion, and justice -- these ideals are not remote and far away, solely within the domain of some unfathomable and unreachable God, but rather, are ideals that can be embodied by humans on earth. For Christians, that embodiment is exemplified by Jesus’s birth -- the birth of the son of God, as Christians would put it. But the underlying theological principle is one that we, as Jews, can also affirm: a life on earth can and should be an expression of the noblest divine ideals.

Christmas in the United States is not primarily a theological event. It’s a cultural one. And it’s that cultural phenomenon with which I’ve had such a complicated relationship since I was a child.

But the secularization of Christmas presents us with a surprising opportunity -- an opportunity that the Rabbis of the Talmud could never have imagined, an idea that never would have occurred to me as a child in Tallahassee. There is something theologically powerful contained in the Christmas story -- an idea that has inspired Christians for thousands of generations, and that, if we’re open to it, might grow to inspire us as well: each of us is the child of God, each an embodiment of the divine, if only we would realize it.

_____

[1] For more, see Peter Schäfer’s book Jesus in the Talmud

[2] For more, see Rabbi Dr. Michael Cook’s book Modern Jews Engage the New Testament, chapter 9: “Christmas: Why the Infancy (Virgin Birth) Stories?”

[3] BT Shabbat 104b

[4] Interestingly, the court also held that a menorah was permissible on government property, similarly arguing for its secular status. | For more, Jonathan Sarna’s essay “Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Letter to the Jewish Community of Teaneck, 1981” in Yehuda Kurtzer & Claire E. Sufrin’s book The New Jewish Canon.

[5] For more, listen to Dr. Rachel B. Gross’s interview on the Judaism Unbound podcast: “Digesting Judaism.”

[6] For more, see Rabbi Dr. Larry Hoffman’s article “Dialogue, Liturgy, and Truth: The Shape of Gifts to Come,” in the journal Worship, Volume 94 (2020).

[7] For more, see Shaul Magid’s discussion of Daniel Matt and Zalman Schachter-Shalomi in Magid’s book American Post-Judaism, chapter 6: “From the Historical Jesus to a New Jewish Christology: Rethinking Jesus in Contemporary American Judaism”