Rise Up Atlanta, currently installed in Freedom Park. Riding my bike by there today, I stopped and talked to the artist, Charlie Brouwer. Atlantans loaned him nearly 200 ladders to build the piece, which is held together by industrial zip-ties. Folding ladders, extension ladders, step stools in every size, color, and function come together in unique variety. A favorite of mine (not clearly visible in the photos) is an American flag-patterned folding ladder near the top of the structure. Mr. Brouwer is able to climb the core of the structure to add more ladders. Get there and check it out!

Saturday, April 30, 2011

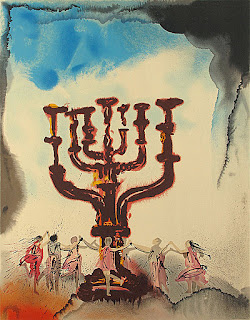

A Many-Pronged Lamp

The campus minister for Reformed University Fellowship asked me recently which aspects of Jewish life were most crucial to my identity. How much was religious/spiritual and how much was peoplehood/cultural?

Indeed, I far more often connect to my Jewish identity through peoplehood than through spirituality. But the instances of spirituality carry far more weight. So in a way, the two sort of balance each other out, the way a pound of feathers balances out pound of lead.

It strikes me that this is a perfect model for Shabbat. Six days we live in our mundane, day-to-day lives (which, incidentally, still carry much valuable work). But one day a week is special, is holy, carries more weight. This is the image of the seven-pronged menorah.

This isn’t to say that experiences of Jewish peoplehood (or Jewish ethics, or Jewish memory) are less valuable than experiences of Jewish spirituality. Rather, it recognizes value in both. And their mutual value only further validates their individual worth. It’s like a great poem—that a single poem can at the same time hold seemingly contradictory meanings and neither one be less true. This is genius.

It further strikes me that this is the reason I want to be a rabbi. I’m a good people-person. I’m relatable, fun, easy-going, likeable. I’m able to connect with people on a six-days-a-week level, on the everyday stuff. And then, if they want, I’m ready to talk about that one-day-a-week stuff, that intimate stuff, that holy stuff.

So I guess I couldn’t say that any one aspect of my Jewish identity is more important than any other. It takes the one to make the other.

Indeed, I far more often connect to my Jewish identity through peoplehood than through spirituality. But the instances of spirituality carry far more weight. So in a way, the two sort of balance each other out, the way a pound of feathers balances out pound of lead.

|

| Orah, Horah, from Salvador Dali's Aliyah, the Rebirth of Israel |

This isn’t to say that experiences of Jewish peoplehood (or Jewish ethics, or Jewish memory) are less valuable than experiences of Jewish spirituality. Rather, it recognizes value in both. And their mutual value only further validates their individual worth. It’s like a great poem—that a single poem can at the same time hold seemingly contradictory meanings and neither one be less true. This is genius.

It further strikes me that this is the reason I want to be a rabbi. I’m a good people-person. I’m relatable, fun, easy-going, likeable. I’m able to connect with people on a six-days-a-week level, on the everyday stuff. And then, if they want, I’m ready to talk about that one-day-a-week stuff, that intimate stuff, that holy stuff.

So I guess I couldn’t say that any one aspect of my Jewish identity is more important than any other. It takes the one to make the other.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

A Hipstamatic Day at Stone Mountain

Have you used the Hipstamatic camera on the iPhone? It takes really cool pictures. So do Leah and I =) Here are photos from our great day at Stone Mountain (click the image for high-res). Are we hip? Maybe. Are we very cute? You tell me!

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Jewish-Arab Coexistence in Israel

At Taste of Limmud, I went to a session on Jewish-Arab coexistence in Israel. The session was specifically about Jewish relations with Arab-Israelis, who are citizens of the State of Israel and live with its borders (not in the Gaza Strip or the West Bank). The discussion was led by Elie Rekhes, head of the Konrad Adenauer Program for Jewish-Arab Cooperation at Tel Aviv University. He answered the question: Why is coexistence important?

Liberal Zionists should think of the challenge of coexistence as an opportunity to show the world how to treat a minority. Jews, of all people, should know what it feels like to be the minority. And to an extent, Israel treats its minority well. Arabic is an official state language and Arabs have full citizenship. Nevertheless, there is much de facto segregation and even a few attempts at de jure segregation (see the so-called Rabbis' Letter, encouraging Jews not to rent or sell homes to non-Jews.) Liberal Zionists cannot accept this sort of blind racism. Have we forgotten that “we were strangers in the land of Egypt?”

In 1948, there were 100,000 Arabs living in the Jewish state. Now there are 1.5 million. This constitutes 20% of Israel’s population. Of that 20%, 83% are Muslim, 8.5% are Christian, and 8.5% are Druze.

Since the 1993 Oslo accords—the acknowledgement of the PLO as the administrative body of the Palestinian people and territories—Arab-Israelis began to reexamine their relationship with Israel. This reexamination took place on three levels: socioeconomic, political, and national.

On the socioeconomic level, the Oslo accords put the Arab-Israelis in a double periphery: on the one hand from their Jewish neighbors and on the other hand from their counterparts in the West Bank. Only 20% of Jews live below the poverty line, whereas 67% of Arabs live below the poverty line. And though Arab-Israelis may have already been accustomed to this economic disparity, they were suddenly also poorer than Arabs in the West Bank, due to increased international support. This dual periphery caused Arab-Israelis to say, “Why not us?”

On the political level, Arabs suddenly recognized their own political impotence. Arabs have full voting rights in Israel, and there are Arab representatives in the Knesset. But because of Israel’s coalition system, Arab parties have very little influence and are often excluded from coalitions and bargain-making. Political focus shifted from the Arab parties in the Knesset to the PLO.

On the national level, the Oslo Accords unified the Israeli-Arabs. Rather than groups of minorities (Christians, Muslims, Druze), they saw themselves as a single indigenous minority with collective rights. They wanted to be acknowledged. Arabs started wondering how Israel’s national symbols pertained to them—the national anthem, with its references to the “Jewish heart;” the flag, with the Star of David; the state emblem, the Menorah. Some scholars have noted this phenomenon by coining the phrase “Israel is democratic for the Jews and Jewish for the Arabs.”

A more recent turning point was the Second Intifada in 2000. The Arabs’ pent-up anger came out in the form of violence, bitterness, and anti-Israel demonstrations. Jewish political opinions moved rightwards, with the emergence and strengthening of political parties like Israel Beitenu (literally: “Israel, our home”), whose 2009 election slogan was “No loyalty, no citizenship.”

Rekhes asserts that, at the very least, there is recognition of the problem. Recent years have seen a call to positive, constructive solutions. There is a growing number of NGOs dealing with Jewish-Arab issues, working the fields of education, economic improvements, and creating space for encounters between Israelis and Arabs. Furthermore, there is government recognition of the need for improved relations, in the form of the Or State Commission of Inquiry (which should be, in my opinion, only a first step) and a Jewish minister of Arab affairs. Finally, there is recognition among world Jewry, in the form of the Inter-Agency Task Force on Arab-Israeli Issues, a coalition of 93 member-organizations.

From this American’s perspective, there is still much work to be done. If there is to be a two-state solution (which seems to be the obvious solution), I wonder about the fate of the Arab-Israelis. And I’m proud that my girlfriend will spend part of our year in Israel working on Arab-Jewish relations.

1) In its Declaration of Independence (the closest thing Israel has to a constitution), Israel is committed to “equal citizenship and due representation” for its Arab inhabitantsCoexistence is difficult because of a paradox of identity. Rekhes described three concentric circles (see image). There is a confounded sense of who is the majority and who is the minority. One of Rekhes’s colleagues put it thus: “An Arab minority with the mentality of a majority, living within a Jewish majority with the mentality of a minority.” This plays out in common feelings of victimhood.

2) In order to preserve Israel’s status as a democracy, co-existence must work

3) It is a moral Jewish imperative

4) It is in Israel’s best economic interests

5) It is important for Israel’s public image

6) It can only strengthen Israel

Liberal Zionists should think of the challenge of coexistence as an opportunity to show the world how to treat a minority. Jews, of all people, should know what it feels like to be the minority. And to an extent, Israel treats its minority well. Arabic is an official state language and Arabs have full citizenship. Nevertheless, there is much de facto segregation and even a few attempts at de jure segregation (see the so-called Rabbis' Letter, encouraging Jews not to rent or sell homes to non-Jews.) Liberal Zionists cannot accept this sort of blind racism. Have we forgotten that “we were strangers in the land of Egypt?”

In 1948, there were 100,000 Arabs living in the Jewish state. Now there are 1.5 million. This constitutes 20% of Israel’s population. Of that 20%, 83% are Muslim, 8.5% are Christian, and 8.5% are Druze.

Since the 1993 Oslo accords—the acknowledgement of the PLO as the administrative body of the Palestinian people and territories—Arab-Israelis began to reexamine their relationship with Israel. This reexamination took place on three levels: socioeconomic, political, and national.

On the socioeconomic level, the Oslo accords put the Arab-Israelis in a double periphery: on the one hand from their Jewish neighbors and on the other hand from their counterparts in the West Bank. Only 20% of Jews live below the poverty line, whereas 67% of Arabs live below the poverty line. And though Arab-Israelis may have already been accustomed to this economic disparity, they were suddenly also poorer than Arabs in the West Bank, due to increased international support. This dual periphery caused Arab-Israelis to say, “Why not us?”

On the political level, Arabs suddenly recognized their own political impotence. Arabs have full voting rights in Israel, and there are Arab representatives in the Knesset. But because of Israel’s coalition system, Arab parties have very little influence and are often excluded from coalitions and bargain-making. Political focus shifted from the Arab parties in the Knesset to the PLO.

On the national level, the Oslo Accords unified the Israeli-Arabs. Rather than groups of minorities (Christians, Muslims, Druze), they saw themselves as a single indigenous minority with collective rights. They wanted to be acknowledged. Arabs started wondering how Israel’s national symbols pertained to them—the national anthem, with its references to the “Jewish heart;” the flag, with the Star of David; the state emblem, the Menorah. Some scholars have noted this phenomenon by coining the phrase “Israel is democratic for the Jews and Jewish for the Arabs.”

A more recent turning point was the Second Intifada in 2000. The Arabs’ pent-up anger came out in the form of violence, bitterness, and anti-Israel demonstrations. Jewish political opinions moved rightwards, with the emergence and strengthening of political parties like Israel Beitenu (literally: “Israel, our home”), whose 2009 election slogan was “No loyalty, no citizenship.”

Rekhes asserts that, at the very least, there is recognition of the problem. Recent years have seen a call to positive, constructive solutions. There is a growing number of NGOs dealing with Jewish-Arab issues, working the fields of education, economic improvements, and creating space for encounters between Israelis and Arabs. Furthermore, there is government recognition of the need for improved relations, in the form of the Or State Commission of Inquiry (which should be, in my opinion, only a first step) and a Jewish minister of Arab affairs. Finally, there is recognition among world Jewry, in the form of the Inter-Agency Task Force on Arab-Israeli Issues, a coalition of 93 member-organizations.

From this American’s perspective, there is still much work to be done. If there is to be a two-state solution (which seems to be the obvious solution), I wonder about the fate of the Arab-Israelis. And I’m proud that my girlfriend will spend part of our year in Israel working on Arab-Jewish relations.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Mysteries of the Seder

With Passover approaching, I’m reminded of a session I went to at Taste of Limmud called “Mysteries of the Seder.” The session was led by Clive Lawton, co-founder of Limmud.

Lawton posits that seder—and more generally, the many, varied complexities of Judaism—is not just kids’ stuff. He pictures an amusement park: somewhere you take your kids because they like to go on the rides, but you wouldn’t choose to go to on your own. Eventually, your kids out grow the amusement park and you both wonder why you continue to come. The seder should not be like this. Instead, the seder should be thought of like the theatre. If your kids are too little, you hire a babysitter and leave the kids at home. Theatre is too sophisticated for a four-year-old, but too important for you to miss it. When your kids are old enough, you bring them to age-appropriate shows—Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz. Then, when they’re older still, you take them to more and more sophisticated plays—Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Waiting for Godot. So too with Jewish experiences. If you simplify them too much, your children will never grow to experience them in their full, beautiful complexity. Lawton puts it very well: “Judaism is something you grow into, not something you grow out of.”

With this as a backdrop, Lawton launched into a sophisticated yet warm discussion on the mysteries of the seder. He talked about the 10 plagues. Here in the middle of the seder, as the excitement has been building, we take a solemn pause to remember the suffering of the Egyptians. It is to remind us that many blessing are brought at the suffering of others. And we don’t simply say “The Egyptians suffered 10 terrible plagues,” but rather take the time to spell them out individually. Take a modern example. We might say: “We think of those who are suffering from the catastrophe in Japan.” But instead, we say, “We think of those who are suffering from the catastrophe in Japan. Those whose homes crumbled in the earthquake. Those whose possessions were washed away in the tsunami. Those who were exposed to nuclear radiation. Those who were afraid at the continuing aftershocks. Those who aren’t able to get clean water and food. Those who are separated from their loved ones. …” In this way, we more fully acknowledge their suffering. This is what the seder asks us to do.

Lawton stressed that the most important thing in the seder is not accuracy but meaningfulness. It doesn’t matter if you follow all the rituals in every detail exactly as they are outlined in the haggadah, so long as you make every bit of your seder meaningful. After all, this is where Judaism gives us room for creativity. Judaism often tells us what to do, but doesn’t often tells us what to think about it. He gave a beautiful illustration using tefillin. The two boxes of tefillin are in fact not identical. Both boxes contain four blessings. In the box you wear on your arm, all four blessings are on one scroll of paper and in one compartment. In the one you wear on your head, each blessing is on an individual scroll and in an individual compartment. This is to show that there is only one thing we are required to do (with our arm) but many ways to think about it (with our head).

Lawton helped answer why we dip twice on Passover. Once, we dip the parsley in salt water and once we dip the marror in charoset. The parsley in salt water reminds us that even when we are feeling fresh and young, like a sprig of parsley, we should remember that life sometimes brings salty tears. On the other hand, when we’re weighed down by bitterness, like the marror, we should remember than can again be sweet, like the charoset. It is to show both sides of one coin.

He gave a midrash to help explain why the charoset—supposed to represent the mortar of slavery—should taste sweet. There’s a midrash that when Pharoah ordered the death of all male Hebrew babies, the Hebrew men went into despair. “Why bother to continue to procreate if Pharoah is only going to kill them?” The men became very “flaccid.” The women, on the other hand, were brave. The dressed in their finest clothes, wore their finest make-up and perfumes, and went to the orchards. There, they beckoned the men to follow and be seduced. Under the orchards, they made love—as in the scroll we read on Passover, Song of Songs. The charoset, therefore, is made of sweet dates, figs, apples, and nuts—to remind us of the sweet love made under the orchards.

Lawton posits that seder—and more generally, the many, varied complexities of Judaism—is not just kids’ stuff. He pictures an amusement park: somewhere you take your kids because they like to go on the rides, but you wouldn’t choose to go to on your own. Eventually, your kids out grow the amusement park and you both wonder why you continue to come. The seder should not be like this. Instead, the seder should be thought of like the theatre. If your kids are too little, you hire a babysitter and leave the kids at home. Theatre is too sophisticated for a four-year-old, but too important for you to miss it. When your kids are old enough, you bring them to age-appropriate shows—Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz. Then, when they’re older still, you take them to more and more sophisticated plays—Romeo and Juliet, The Crucible, Waiting for Godot. So too with Jewish experiences. If you simplify them too much, your children will never grow to experience them in their full, beautiful complexity. Lawton puts it very well: “Judaism is something you grow into, not something you grow out of.”

With this as a backdrop, Lawton launched into a sophisticated yet warm discussion on the mysteries of the seder. He talked about the 10 plagues. Here in the middle of the seder, as the excitement has been building, we take a solemn pause to remember the suffering of the Egyptians. It is to remind us that many blessing are brought at the suffering of others. And we don’t simply say “The Egyptians suffered 10 terrible plagues,” but rather take the time to spell them out individually. Take a modern example. We might say: “We think of those who are suffering from the catastrophe in Japan.” But instead, we say, “We think of those who are suffering from the catastrophe in Japan. Those whose homes crumbled in the earthquake. Those whose possessions were washed away in the tsunami. Those who were exposed to nuclear radiation. Those who were afraid at the continuing aftershocks. Those who aren’t able to get clean water and food. Those who are separated from their loved ones. …” In this way, we more fully acknowledge their suffering. This is what the seder asks us to do.

Lawton stressed that the most important thing in the seder is not accuracy but meaningfulness. It doesn’t matter if you follow all the rituals in every detail exactly as they are outlined in the haggadah, so long as you make every bit of your seder meaningful. After all, this is where Judaism gives us room for creativity. Judaism often tells us what to do, but doesn’t often tells us what to think about it. He gave a beautiful illustration using tefillin. The two boxes of tefillin are in fact not identical. Both boxes contain four blessings. In the box you wear on your arm, all four blessings are on one scroll of paper and in one compartment. In the one you wear on your head, each blessing is on an individual scroll and in an individual compartment. This is to show that there is only one thing we are required to do (with our arm) but many ways to think about it (with our head).

Lawton helped answer why we dip twice on Passover. Once, we dip the parsley in salt water and once we dip the marror in charoset. The parsley in salt water reminds us that even when we are feeling fresh and young, like a sprig of parsley, we should remember that life sometimes brings salty tears. On the other hand, when we’re weighed down by bitterness, like the marror, we should remember than can again be sweet, like the charoset. It is to show both sides of one coin.

He gave a midrash to help explain why the charoset—supposed to represent the mortar of slavery—should taste sweet. There’s a midrash that when Pharoah ordered the death of all male Hebrew babies, the Hebrew men went into despair. “Why bother to continue to procreate if Pharoah is only going to kill them?” The men became very “flaccid.” The women, on the other hand, were brave. The dressed in their finest clothes, wore their finest make-up and perfumes, and went to the orchards. There, they beckoned the men to follow and be seduced. Under the orchards, they made love—as in the scroll we read on Passover, Song of Songs. The charoset, therefore, is made of sweet dates, figs, apples, and nuts—to remind us of the sweet love made under the orchards.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)